The Civil War Begins At The Battle Of First Bull Run

Forces Overview

Union Forces:

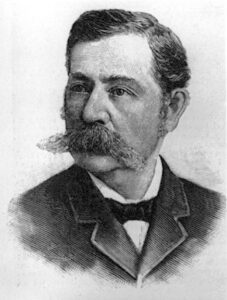

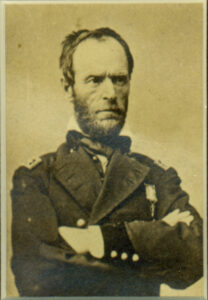

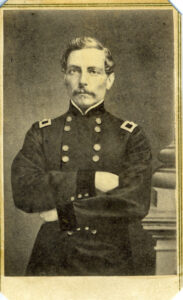

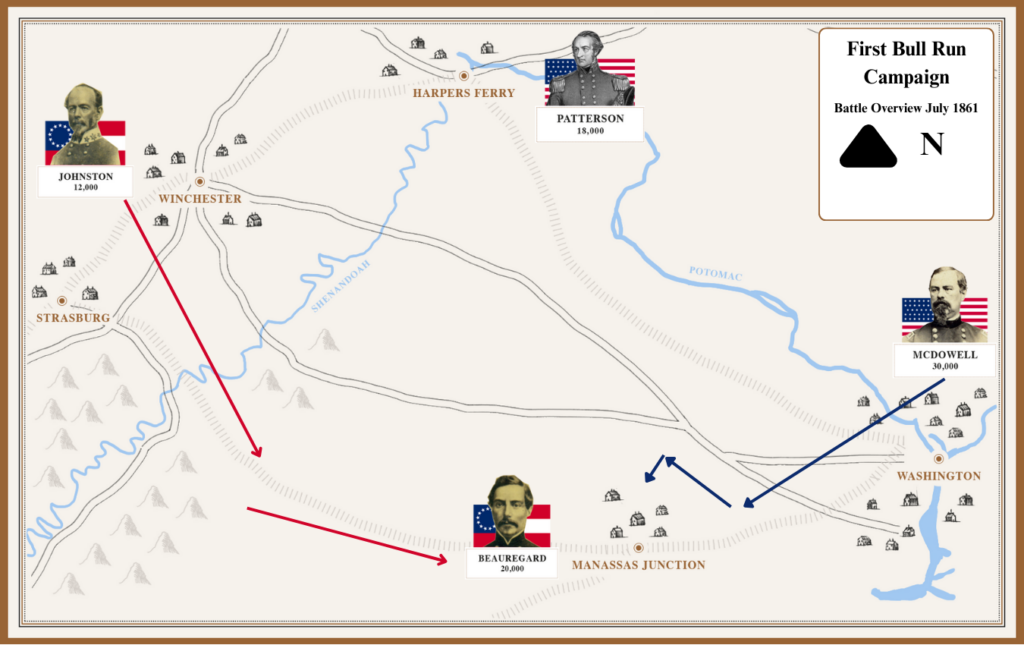

The Army of Northeastern Virginia under General McDowell made up the bulk of Union Forces. The army was composed of 36,000 troops divided into five divisions, these divisions were further divided into 3 to 5 brigades. There was also another army of 18,000 under Major General Robert Patterson, to prevent any incursion through Harpers Ferry. Click on each photo for more information:

Other notable officers include:

Confederate Forces:

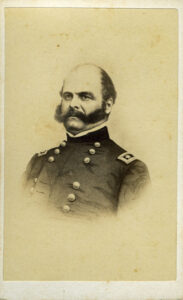

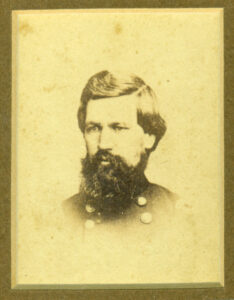

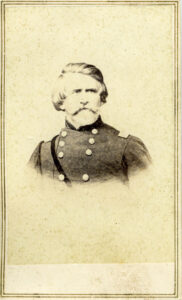

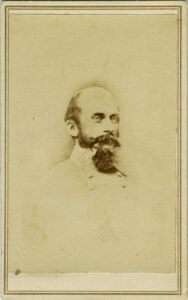

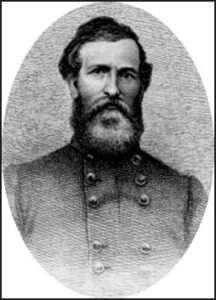

The Army of the Potomac made up the bulk the of Confederate forces. Commanding the army was General P.G.T. Beauregard, the army was organized into seven infantry brigades under the following commanders, click each photo for more information:

The Army of the Shenandoah also made up a sizable portion of Confederate Forces. This army was under the command of Joseph E. Johnston. The army was composed of 12,00 men and was split into four brigades.

The Battle Of First Bull Run – July 21, 1861

Events Leading Up to the Battle

McDowell’s army begins the 35 mile trek from Washington to Manassas around 2PM on July 16. It marches at a snail’s pace in blistering heat, first to Centerville, Va. and then west along the Warrenton Pike. To meet this threat, Beauregard stations his troops along the meandering southern banks of Bull Run Creek, a natural line of defense.

On the morning of July 18, 1861, McDowell makes his first move, probing the right flank of the Confederate lines at Blackburn’s Ford, where General Daniel Tyler is repulsed by CSA General James Longstreet.

That same day, Joe Johnston’s army slips away from Patterson in the Shenandoah Valley, marches 23 miles to Piedmont, where it boards trains for the 57 mile trip to Manassas Junction and the link up with Beauregard.

Finally on July 20 the two “green” armies are concentrated north and south of the Warrenton Pike and eager to engage in what will become the first major battle of the war.

Each side will send roughly 18,000 men into the field on July 21.

Key Events: First Bull Run

| July | Time | Headlines |

| 15 | Patterson moves his troops to Winchester to pin Joe Johnston | |

| 16 | 2pm8pm | McDowell marches out of WashingtonSpy Rose Greenhow’s message warns Beauregard to prepare |

| 18 | am | Tyler attacks at Blackburn’s Ford; Longstreet pushes him back.Johnston marches 23 miles to piedmont and boards trains |

| 19 | Johnston arrives in Manassas at 1pm and links with Beauregard | |

| 20 | pm | Both sides concentrated and arrayed for battle |

July 21, 1861 – Morning

McDowell Seizes the Advantage Early in the Battle

Attack by Hunter Drive Evans off Mathew’s HIll

Attack by Hunter Drive Evans off Mathew’s HIllBoth commanders plan to send their left wing forces against what they regard as vulnerabilities on their opponent’s right. But McDowell gets the early jump in the morning, and forces Beauregard to defend rather than attack as planned.

<br>

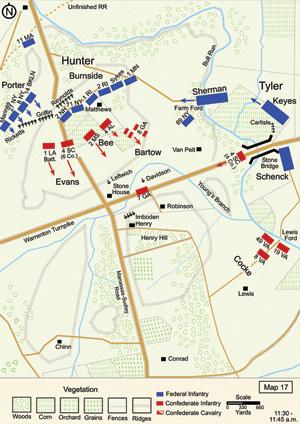

The Union attack commences about 5:15am from the Sudley Church, roughly two miles north of the Warrenton Pike. Some 20,000 troops under the command of Major General David Hunter plunge south in parallel to the Manassas-Sudley Springs Road toward Matthew’s Hill, defended by a small rebel contingent of 1100 men under Colonel “Shanks” Evans of South Carolina.

<br>

Evan’s stand against Colonel Ambrose Burnside’s lead brigade buys the Confederates precious time to begin assembling an organized resistance further south, across the Warrenton Pike.

<br>

During the action General Hunter is shot in the face and turns his Second Division command over to Colonel Andrew Porter.

<br>

Evans is able to hold out until 11:30am, when Union troops under Colonels William Sherman and Erasmus Keyes assault his right flank, forcing a general retreat to Henry Hill.

By noon on July 21, the battle is shaping up as will for the North.

Time: July 21, 1861 – 1-3PM

The Confederates Make a Heroic Stand on Henry Hill

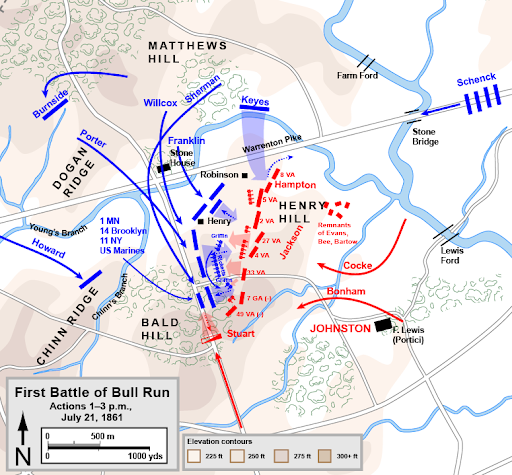

With the Confederates in flight toward Henry Hill, McDowell makes a tactical error that will prove decisive. Instead of immediately sending his infantry against the hill, he decides to slow the attack and use his artillery to degrade the rebel defenses.

Captains James Ricketts and Charles Griffin set up their batteries on Dogan Ridge and begin sending 12 lb. cannon balls over the heads of the Federal troops and into Henry Hill, some 1400 yards to their east.

As this cannonade plays out, Joe Johnston is able to assemble a defensive line along Henry Hill, with cavalry units under Colonels Wade Hampton and Jeb Stuart anchoring the flanks, and a central infantry barrier composed of units led by Brigadier Generals Tom Jackson and Barnard Bee and Colonel Francis Bartow.

Jackson’s battlefield eccentricities are already on display, sucking on a lemon, “old blue light” eyes shining, right arm pointing straight upward on behalf of divine guidance, and a characteristic response to Bee when informed of the impending danger: “then we will give them the bayonet!”

In the early afternoon, McDowell orders his batteries to advance from Dogan Ridge, across the Warrenton Pike to positions adjacent the Henry House, for close order fire on the hill 300 yards to the east. This precipitates a fierce exchange between Rickett’s and Jackson, two of the war’s most accomplished artillery experts.

It also claims the life of the widow Judith Henry, an 85 year old invalid, trapped in her house, surrounded by cannons. She becomes the first of roughly 50,000 civilian casualties of the war.

Amidst the screaming shells and fogging smoke, Keyes and Sherman resume their advance on Henry Hill, joined now by brigades under Colonels William Franklin, Orlando Willcox and Andrew Porter.

Bartow’s horse is shot from under him on the hill, before he is struck and killed by shrapnel. Bee is next to fall, suffering a wound to the abdomen which proves mortal the following day. But just before Bee is hit, he rallies his men with words that will immortalize the commander on his right flank:

There is Jackson standing like a stone wall. Let us determine to die here, and we will conquer. Rally behind the Virginians!

The heroic stand by Jackson, Bartow and Bee on Henry Hill stops the Union momentum in the mid-afternoon, and sets the stage for a decisive Confederate counter-attack.

This occurs soon after Colonel Oliver Otis Howard brings his forces up on the Union right, along Chinn Ridge, to further pressure the rebel’s left flank.

Time: July 21, 1861 4PM – Dusk

The Confederates Turn the Tide and Win the Battle

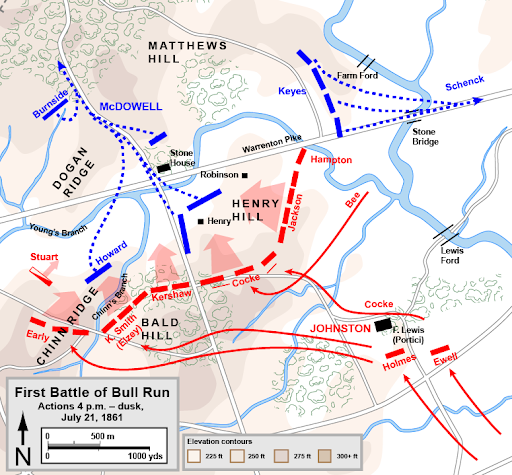

With the danger to his right wing stemmed on Henry Hill, CSA Commander Joe Johnston plots a counter-offensive to roll up the entire Union army.

It involves a two-pronged attack – with his right flank under Jackson sweeping downward from Henry Hill to the west, and his left flank advancing north along the Manassas-Sudley Springs vector.

To strengthen his left flank, Johnston sends brigades under Colonel Jubal Early and Arnold Elzey, who assumes command after General Kirby Smith is severely wounded in the neck.

Around 4pm, Johnston springs his trap.

Luck favors his right wing thrust when Union Major William Barry orders Griffin not to fire on approaching troop decked out in light blue uniforms – who turn out to be Virginians. They seize the federal guns, and are soon joined in overrunning federal defenses at the Henry House by Jackson’s men, racing across the field sounding full-throated Rebel Yells.

To the southwest, General O.O. Howard’s is also taken by surprise by Elzey and Early and driven off Chinn Ridge – precipitating a general retreat by McDowell’s entire army. Some flee northward toward their original staging area at Sudley Springs. Others scamper west across the Stone Bridge over Bull Run toward Centerville, and, from there, back to Washington.

Some 1300 Union soldiers are captured in flight, along with New York Congressman Alfred Ely, who, like many DC residents has come out to observe the battle from afar. For his follly, Ely will spend five months in Richmond’s Libby Prison before being returned in a hostage swap.

Time: July 21, 1861 4PM – Dusk

Postscript on First Bull Run

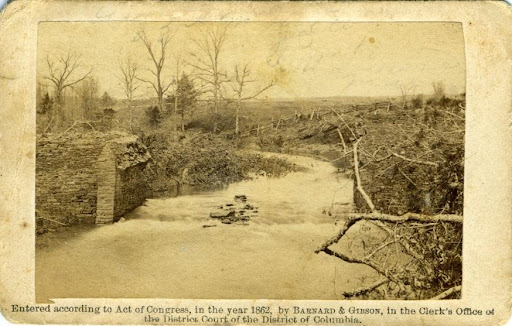

The Stone Bridge along the Warrenton Pike Crossing Bull Run Creek

The Stone Bridge along the Warrenton Pike Crossing Bull Run CreekThe Battle of First Bull Run opens America’s eyes to what has been well known to European nations for decades – the level of carnage that follows when two large and well equipped armies fight it out from dawn to dusk on open ground.

On July 21, 1861, some 847 American soldiers lose their lives; another 2,706 are wounded; and 1325 are missing or captured.

Casualties: Battle of First Bull Run

| Union | CSA | Total | |

| Total Engaged | 18,000 | 18,000 | 36,000 |

| Total Casualties | 2,896 | 1,982 | 4,878 |

| Killed | 460 | 387 | 847 |

| Wounded | 1,124 | 1,582 | 2,706 |

| Missing/Captured | 1,312 | 13 | 1,325 |

| Notables Killed | — | Bartow, Bee |

These numbers pale, of course, relative to the butcher’s bills associated with the Napoleonic Wars. At Borodino, for example, the combined losses on September 7, 1812, between the French and Russian armies, total some 75,000 soldiers along with 70 general officers.

Still, America’s 3,553 killed and wounded at the Battle of First Bull Run far exceed anything experienced during the entire Revolutionary War. The highest single day casualty total in that conflict is recorded on August 16, 1780, at the Battle of Camden, SC – where 900 are killed or wounded. The count at the pivotal US victory at Saratoga, NY, is a mere 330, on October 7, 1777.

American Casualties in Revolutionary War Battles

| Camden, SC 8/16/80 | Saratoga, NY, 10/7/77 | |

| Total Engaged | 3,700 | 15,000 |

| Total Casualties | 1,900 | 330 |

| Killed | 240 | 90 |

| Wounded | 660 | 240 |

| Missing/Captured | 1,000 | — |

When West Point graduates like Irwin McDowell and Joe Johnston send their armies into the field on July 21, 1861, their formations and tactics mirror those utilized from the American Revolution through the Napoleonic era. Long rows of troops, two columns deep, marching side by side to confront a similarly arrayed adversary.

But what has changed in the interim – and will change even more dramatically during the course of the American war – is the firepower these brave marching troops will encounter. The old 1842 Smoothbore musket, accurate to 100 yards in the hands of the average soldier, gives way to the 1861 Springfield with rifled barrels, accurate to 300 yards and beyond. Rifling has also improved the basic “1857 Napoleon 12 lb. cannon” which, as both Ricketts and Jackson demonstrate at Bull Run, are now deadly from up to a mile away.

Both methods of killing will improve throughout the conflict. The “Sharps Repeating Rifle” will be capable of firing 8-10 rounds per minute vs. the laborious 7-step Springfield drill required to first 2-3 rounds per minute. The Whitworth breech-loading cannon will hurl a 12 lb. ball up to 2800 yards, and the popular Parrott Gun will achieve 1900 yards with a 20 lb. projectile.

The effects of this increased firepower will soon be evident. On September 17, 1862, at the Battle of Antietam, 3,654 will die and another 17,292 will be wounded. At Gettysburg, over the first three days of July 1863, 7,864 will be killed and another 27,224 injured.

Americans North and South will continue to learn about the cost of warfare as the fighting drags on over four more years. But it is at First Bull Run, on July 21, 1861, that the initial “loss of innocence” dawns on the public and the politicians.

As McDowell’s beaten troops filter willy-nilly into Washington, all notions of a glorious three month “On to Richmond” war begin to vanish. Lincoln’s “green army” has proven itself for the first, but certainly not the last time, to be just that. On July 25, Lincoln sacks McDowell and hands command over the Army of the Potomac to General George B. McClellan, with orders to convert the soldiers from rag-tags to professionals. McClellan however proves to an arrogant figure (referred to as the “Little Napoleon”), with racist views toward blacks, sympathy for the states rights arguments of the South, open disdain for the President, and political ambitions of his own. McClellan will be replaced after 16 months in command, and will ultimately run against Lincoln in the 1864 race, as a “peace Democrat.”

If the North is shocked by the loss at Bull Run, the South, is elated by its victory but also totally uncertain about how to follow it up.

Optimists argue that the stinging defeat will convince the North to simply back off, and leave the South alone, to go its own way, But this never happens and the war carries on over four more years.

To learn more about the battle you might want to read:

We Shall Meet Again – The First Battle of Manassas July 18-21, 1861 by JoAnna McDonald

Battle at Bull Run by William C. Davis

Donnybrook – The Battle of Bull Run, 1861 by David Detzer

For a video tour of the battle: Shock and Awe at Bull Run.