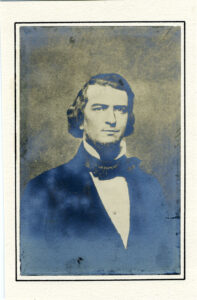

May 22, 1856: Abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner Is Nearly Caned To Death By Irate Southern Congressman Preston Brooks.

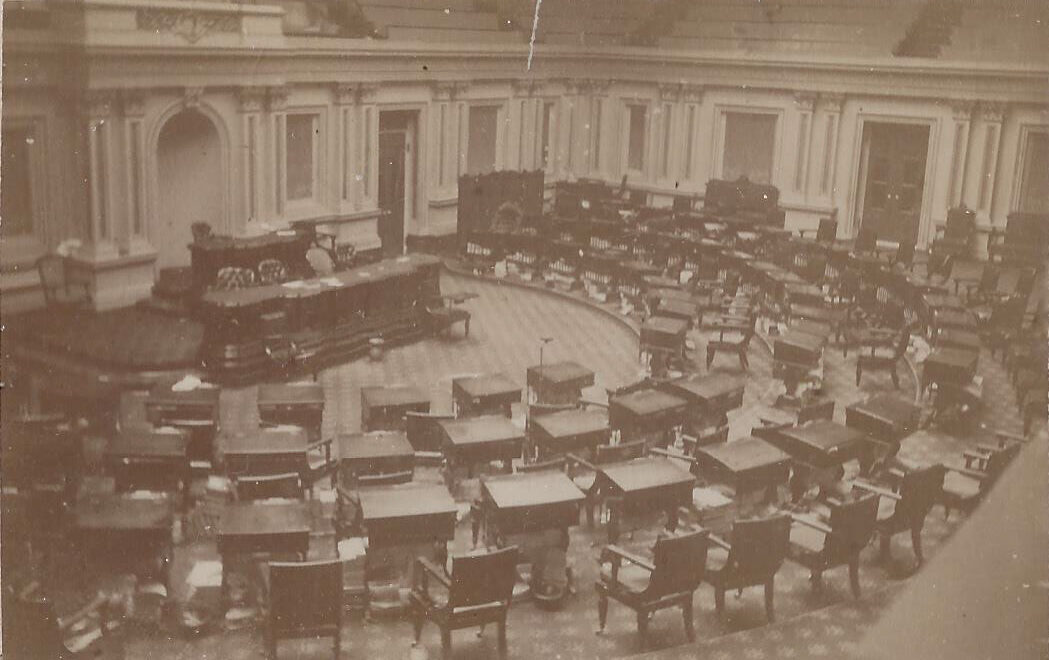

You are there: Two days after delivering a vitriolic speech condemning the “Slavocracy” of the South, Charles Sumner is seated at his desk on the floor of the Senate when struck some thirty times with a gutta percha cane wielded by Congressman Preston Brooks.

Sumner’s speech titled, Crimes Against Kansas, runs over two days and details the illegal attempts by the “Missouri Ruffians” to insure that the new territory is admitted to the Union as a Slave State. His indictment includes fraudulent elections and organized violence aimed at Free State settlers — all orchestrated by pro-Southern Presidents Pierce and Buchanan and two senatorial conspirators, Stephen Douglas and Andrew Butler.

After Butler interrupts his speech on 37 occasions, Sumner turns his spleen on the South Carolina Senator mocking his speaking difficulties after suffering a recent stroke:

With regret, I come again upon Mr. Butler, who overflowed with rage at the simple suggestion that Kansas had applied for admission as a State; and, with incoherent phrases discharged the loose expectoration of his speech, now upon her representative, and then upon her people.

When Sumner’s violation of Senate decorum escapes a reprimand, Congressman Charles Brooks, a second cousin of Butler and a South Carolina man, takes matters into his own hands. Accompanied by Congressman Henry Edmondson and Lawrence Keitt, the latter waving a pistol, Brooks delivers his frontier justice on the seated Sumner:

I…gave him about 30 first rate stripes. Toward the last he bellowed like a calf.

I wore my cane out completely, but saved the head which is gold.

Sumner is helped to an anteroom, where a doctor is called to put stitches into his wounds. His shirt collar is soaked in blood, as is his suit jacket. When the work is completed, Senator Henry Wilson helps him to a carriage and takes him home to bed.

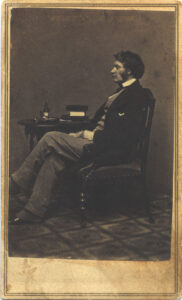

Sumner’s injuries, both physical and psychological, are long-lasting, and three years pass before he is able to return to the Senate to pursue his agenda as a Radical Republican.

Immediate reactions to the assault are diametrically opposed by region. In his New York Evening Post editor William Cullent Bryant writes:

The South cannot tolerate free speech anywhere, and would stifle it in Washington with the bludgeon and the bowie-knife, as they are now trying to stifle it in Kansas by massacre, rapine, and murder. Are we too, slaves, slaves for life, a target for their brutal blows, when we do not comport ourselves to please them?

On the other hand, Brooks is hailed as a hero across the South, for “lashing the Senate’s vulgar abolitionists into submission.” Scores of citizens respond by sending him “replacement canes” to continue his good work.

After Brooks is arrested and released on bail, a House committee is formed to investigate the incident, taking testimony from twenty-seven witnesses and reporting its findings on June 2, 1856. It calls for Brooks to be expelled and both Keitt and Edmondson to be censured.

A bitter debate follows, with several House members challenging each other to duels, before a 121-95 vote to expel Brooks falls short of the two-thirds majority needed to act. In the end, Brooks resigns on his own after paying a $300 fine for damages, while Keitt is censured and Edmondson is acquitted.

Keitt’s South Carolina constituents, however, refuse to accept his act, and immediately vote him back into office. He returns to the House, before dying suddenly in January 1857 after a bout of the croup.