September 2, 1864: The Fall Of Atlanta

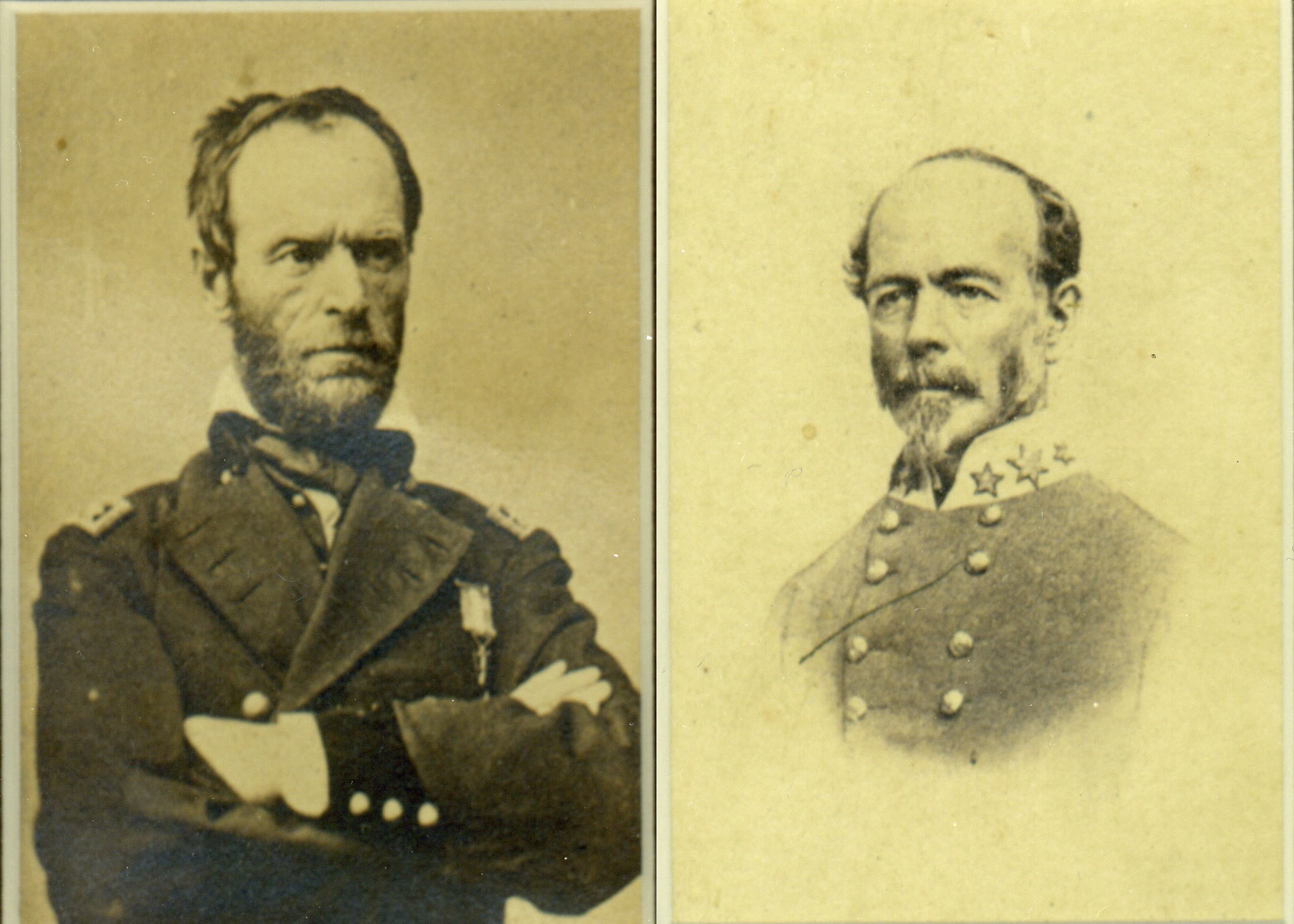

You are there: Fourteen months after the Confederate losses at Gettysburg (7/3/63) and Vicksburg (7/4/63), the fall of Atlanta seals the fate of the deep south. The battle matches two of the leading generals of the entire war: the rebels Joseph Johnston and William Tecumseh Sherman for the Union.

Johnston is born in 1807 at Farmville, Virginia near the headwaters of the Appomattox River. His father Peter, a veteran of the Revolutionary War, is a judge. He attends Abingdon Academy before graduating from West Point in 1829. After serving in the Black Hawk and Second Seminole wars he takes part in the 1847 conquest of Mexico City where he is wounded twice and brevetted a Colonel. However, his effort to have his brevet rank made permanent is turned down by Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, which begins years of tension between the two men.

When the Civil War breaks out, the 54 year old Johnston, now a Brigadier General, earns added fame on April 21, 1861, when his reinforcements, including Stonewall Jackson’s brigade, lead the victory at First Bull Run. After that, Davis advances him to full General, the highest rank in the Confederate Army. But even this honor falls flat when three other men (Sam Cooper, AS Johnston and RE Lee) are placed above him in the hierarchy. He tells Davis that his “fair fame as a soldier and a man is tarnished” by the slight.

Despite this personal rancor, Davis repeatedly calls upon Johnston for crucial assignments.

In June 1862 he commands the defense of Richmond against McClellan, before being wounded at Seven Pines and replaced by RE Lee. After recovering he takes over the Department of the West, but is unable to prevent the fall of Vicksburg in July 1863 or the loss of Chattanooga in November 1864. When Johnston, with some justification, blames Braxton Bragg for the latter defeat, Davis hands him the Army of Tennessee to defend Georgia against his 44 year old adversary, William Tecumseh Sherman.

Known as “Cump,” Sherman grows up in Ohio after losing his father, a Supreme Court Justice, at age nine. He is raised by a neighbor, Thomas Ewing, later a US Senator, who gets him admitted to West Point at sixteen. After graduating, he serves for more than a decade before leaving the army in 1853, first to pursue real estate interests in San Francisco, then in 1859 as Superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy (later LSU). But when Ft. Sumter falls, he volunteers and is given a commission as Colonel of the 13th US Infantry in May 1861 with help from younger brother John, a US Senator from Ohio.

His brigade performs so well in July at First Bull Run, that President Lincoln advances him to Brigadier General and suddenly gives him command of the Department of the Cumberland. But Sherman is overwhelmed by the assignment and exhibits the first signs of a bi-polar condition that will plague him off and on. Almost immediately he asks to be relieved, and newspaper reports of his behavior mention “insanity:”

He talks incessantly while never listening, all the while repeatedly making quick,

sharp…odd gestures, pacing the floor, chain-smoking cigars, twitching his red

whiskers — his coat buttons — playing a tattoo on the table with his fingers. All

in all he is a bundle of nerves all strung to their highest tension.

He bounces back, however, and in February 1862, acts as an advisor to Ulysses Grant (whom he ranks) in his victory at Ft. Donelson. In turn, Grant selects him to lead his 5th Division at Shiloh, where his Day 2 assaults drive the Confederates off the field. From then on, the tandem of Grant and Sherman will dictate the fate of the Union Army.

On March 1, 1864, Lincoln elevates Grant to overall command of the Union army and he taps Sherman to lead his 110,000 man army against Joe Johnston’s 45,000 defenders. He begins from Chattanooga on May 4, 1864, the same date that Grant kicks off his Overland march in Virginia against Lee. Both employ the same tactics – a series of spontaneous stand-up fights along a southerly path, followed by flanking movements to keep the enemy retreating.

The first clash in Sherman’s 120 mile trek occurs on May 15 where he forces Johnston to retreat from Resaca. He then skips past a strong defensive trap Johnston has laid out at Cassville and on May 25-28 fights another stand-off battle at Dallas, 30 miles west of Atlanta.

With no more westward flanking opportunities left, Sherman heads directly toward Marietta where, on June 27, the largest battle of the campaign is fought at Kennesaw Mountain. With about 17,000 men engaged on each side, Johnston achieves a tactical win, inflicting 3,000 Union casualties against only 500 on their side. But strategically Sherman is simply slowed, not stopped.

In Richmond, President Davis has watched the series of retreats by Johnston with growing frustration, despite his 2:1 disadvantages in manpower. On July 17, his patience runs out and he sends Johnston a telegram ordering him to turn the army over to General John Bell Hood. As head of the Texas Brigade, Hood is renowned for his offensive tactics at the Peninsula, Antietam and Chickamauga. His creed favors abandoning breastworks and marching forward into enemy fire. In the process he himself loses use of his left arm after being wounded at Gettysburg and has his right leg amputated after Chickamauga.

Around Atlanta he lives up to his reputation while almost bleeding his army dry. On July 20 at Peachtree Creek he loses 5,000 men while failing to even budge General Thomas. His assault east of Atlanta on July 22 adds 7,500 more casualties. After another 5,000 Confederates fall during Sherman’s July 28 attack west of the city, Hood is down to 35,000 troops.

By this time, only 3,000 of the city’s population of 22,000 remain in place. One Marcus Bell, an aide to General Howell Cobb, describes their suffering in an August 11 letter to his wife:

I arrived at home yesterday afternoon, when huge and fiery missiles of death were

flying in thick and fast upon this city. I went over to our cemetery lot yesterday and

while I was there I could hear the firing in the heavy skirmish fight broken loose on

our extreme east – (where) I beheld the graves of brother Henry Bibb Bell, killed in

Tennessee with ‘Duty unto Death’ on his tomb, and of father. I gave my heart up

to sadness at the cruelties of man.

This morning I go about town.The shells have fallen in our front and rear yards

– struck McMillan’s well and yard; one went through Charlie Schuartz’s house

and one through John Butler’s well and into the kitchen and torn our wash pot

into flinders. Mrs. D.B. Dodd’s opposite to us, has been ploughed six times with

huge bombs. One burst right plumb in their side gate, one near the other gate.

Poor Della Pitman superintended yesterday the digging of a big cave right this

side of (her) kitchen. It is finished – it is now full of women and children. Nearly

every family has one. You go over the city and everywhere during the shelling you

see poor and rich men, women and children now and then poke their heads out of

the little doors of these dens.

The old Methodist church was pierced by shells four or five times, the bookcases and

benches shattered awfully. The parsonage riddled severely. Judge William Ezzard’s

and the Smith houses are injured badly. All the poorer people here ‘drew’ rations.

There is no business of consequence. The burning swept all of the Connally block up

to that other burning. A man, Peter Long, was struck in both legs and died in about

ten hours. Mrs. Weaver, on Walton Street, was in her kitchen with her child nearby

and the shell ripped through the walls and tore her child to pieces.

Church going here has almost ceased – so with business. The people wander about

in distress. I will try and go to see your father and mother before I receive new orders.

Oh! What a fate is Atlanta’s! I hope the day of relief is near at hand! My love to all,

Yours every truly, Marcus A. Bell Prayer for peace…

Sherman has Hood almost completely surrounded by the last day in August when the final battle takes place at Jonesboro, 15 miles south of the city. Hood manages to save what’s left of his army, while surrendering Atlanta.

On September 2, 10 year old Carrie Berry records her thoughts in her diary:

We couldn’t sleep last night. The Confederate army set fire to a train full of ammunition,

and the explosion and fire kept us all awake. All day people have been looting stores,

trying to get food before the Union Army arrives. We were afraid the soldiers would

treat us very badly, but they have behaved very well so far. I think I shall like them.

The fall of Atlanta adds to Sherman’s fame and earns him a promotion to Major General in the Regular Army. It also assures Lincoln’s win in the 1864 presidential race over his “Copperhead” opponent, George McClellan. He sets fire to all government and military structures in Atlanta and, after momentarily chasing Hood, he begins his famous “march to the sea,” taking Savannah on December 20, 1864.

Meanwhile Hood heads to Tennessee and wrecks what is left of his army at the Battle of Franklin where six of his generals are killed and another six wounded in shows of foolish bravado.

And what of Joseph Johnston? In a supreme irony, critics of Jefferson Davis essentially force him to restore Johnston to command of the troops remaining after the fall of Savannah. But it is a shadow army and will surrender to Sherman on April 26, 1865, in North Carolina.

It is thus Sherman who has the last word on the outcome:

War is cruelty. There is no use trying to reform it.

The crueler it is the sooner it will be over.