Lincoln’s Cooper Union Speech

In October 1859 Abraham Lincoln accepted an invitation to lecture at Henry Ward Beecher’s church in Brooklyn, New York, and chose a political topic which required months of painstaking research. His law partner William Herndon observed, “No former effort in the line of speech-making had cost Lincoln so much time and thought as this one,” a remarkable comment considering the previous year’s debates with Stephen Douglas.

The carefully crafted speech examined the views of the 39 signers of the Constitution. Lincoln noted that at least 21 of them — a majority — believed Congress should control slavery in the territories, rather than allow it to expand. Thus, the Republican stance of the time was not revolutionary, but similar to the Founding Fathers, and should not alarm Southerners, for radicals had threatened to secede if a Republican was elected President.

When Lincoln arrived in New York, the Young Men’s Republican Union had assumed sponsorship of the speech and moved its location to the Cooper Institute in Manhattan. The Union’s board included members such as Horace Greeley and William Cullen Bryant, who opposed William Seward for the Republican Presidential nomination. Lincoln, as an unannounced presidential aspirant, attracted a capacity crowd of 1,500 curious New Yorkers.

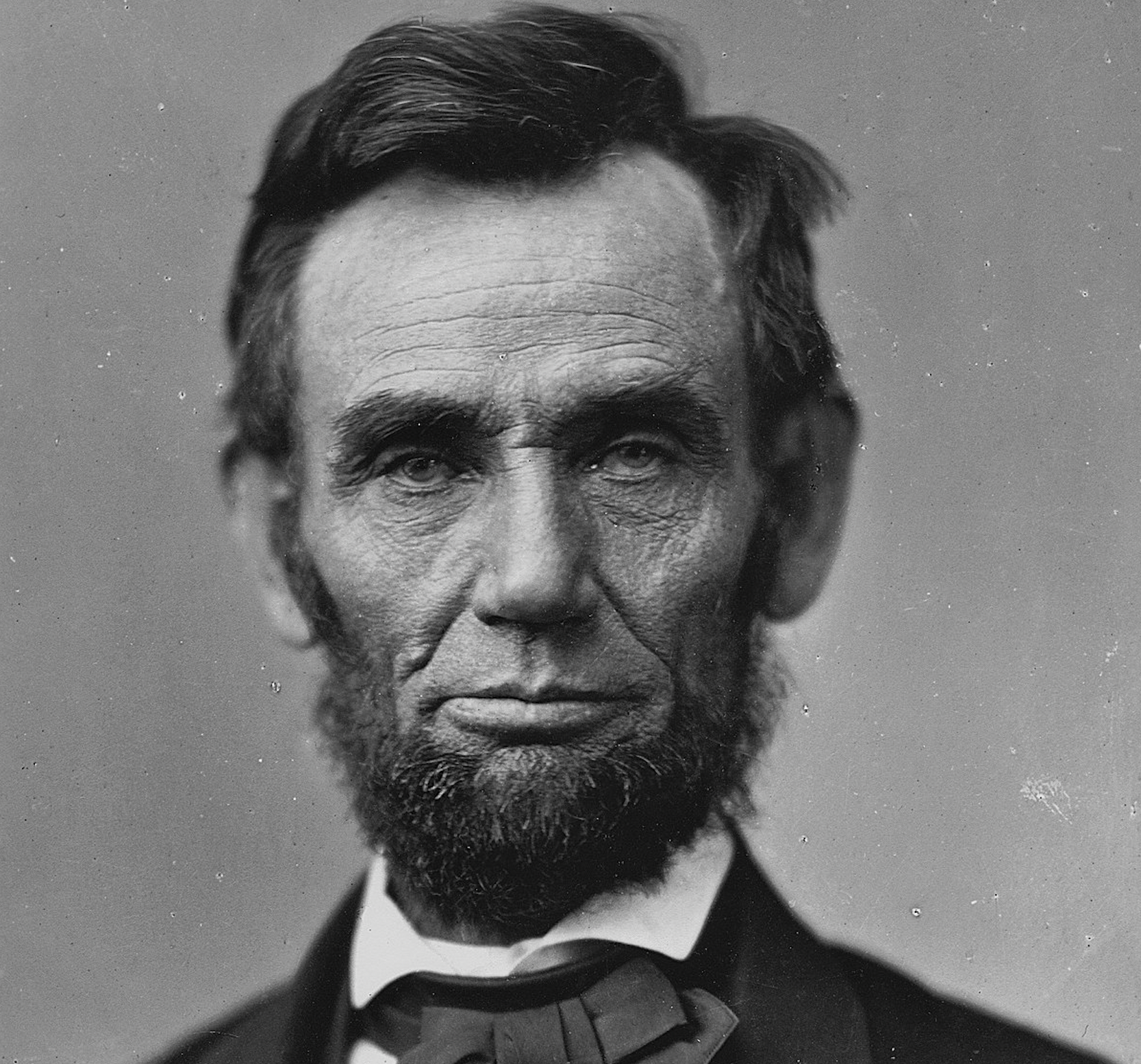

An eyewitness that evening said, “When Lincoln rose to speak, I was greatly disappointed. He was tall, tall, — oh, how tall! and so angular and awkward that I had, for an instant, a feeling of pity for so ungainly a man.” However, once Lincoln warmed up, “his face lighted up as with an inward fire; the whole man was transfigured. I forgot his clothes, his personal appearance, and his individual peculiarities. Presently, forgetting myself, I was on my feet like the rest, yelling like a wild Indian, cheering this wonderful man.”

Herndon, who knew the speech but was not present, said it was “devoid of all rhetorical imagry.” Rather, “it was constructed with a view to accuracy of statement, simplicity of language, and unity of thought. In some respects like a lawyer’s brief, it was logical, temperate in tone, powerful — irresistibly driving conviction home to men’s reasons and their souls.”

The speech electrified Lincoln’s listeners and gained him important political support in Seward’s home territory. Said a New York writer, “No man ever before made such an impression on his first appeal to a New York audience.” After being printed by New York newspapers, the speech was widely circulated as campaign literature.

Easily one of Lincoln’s best efforts, it revealed his singular mastery of ideas and issues in a way that justified loyal support. Here we can see him pursuing facts, forming them into meaningful patterns, pressing relentlessly toward his conclusion.

With a deft touch, Lincoln exposed the roots of sectional strife and the inconsistent positions of Senator Stephen Douglas and Chief Justice Roger Taney. He urged fellow Republicans not to capitulate to Southern demands to recognize slavery as being right, but to “stand by our duty, fearlessly and effectively.”