June 27, 1844. The Founder Of The Mormon Religion, Joseph Smith, Is Murdered In Carthage, Illinois.

You are there: Joseph Smith’s quest to lead his followers in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints to their “New Jerusalem” destination ends suddenly in a flurry of gunshots fired by an angry mob in Carthage, Illionis.

Born in 1805, Joseph Smith, Jr., grows up in a family of Christian mystics in western New York, the epicenter of revivalist meetings during the Second Great Awakening period. He is caught up in this religious fervor, and as a youth experiences a vision of his personal salvation which he begins to share with others in his community.

He tells of being visited by an angel named Moroni in 1823, who reveals the location of a sacred book comprised of gold plates with Egyptian writing by the prophet, Mormon. He then describes his use of a “seer stone” to translate the engravings on the plates. The result is The Book of Mormon, a history of a long vanished Christian community living in America from roughly 500BC to 500AD. While skeptics challenge Smith’s testimony, some 5,000 copies of his book are printed and distributed around Smith’s home town of Palmyra, New York, in 1830.

One result of the book is a quest to locate the land where these aboriginal Christians lived and, once there, to build a new “American Jerusalem.” In 1831 the search begins with Smith leading some of his followers to Kirtland, Ohio, while others move further west to Missouri.

Those in Kirtland build their holy Tabernacle and develop the surrounding town itself, which prospers until 1838. At that point the collapse of a bank Smith opens to fund the community causes internal dissension, with some Mormons dropping out to form their own congregation.

Protesters also tar and feather both Smith and his close associate Sidney Rigdon.

Those who remain loyal to Smith then accompany him to the western edge of Missouri around Jackson County, a location he predicts for the Second Coming of Christ. By the time he arrives, however, most of the Mormons there have been driven out by locals who claim they are trying to take over the land, the economy and the government.

On July 4, 1838, a speech by Rigdon announces the Mormon’s determination to resist any further harassment:

It shall be between us and them a war of extermination; for we will follow them until

the last drop of their blood is spilled; or else they will have to exterminate us, for we

will carry the seat of war to their own houses and their own families, and one party or

the other shall be utterly destroyed.

Rigdon’s gauntlet is picked up by Lilburn Boggs, the Governor of Missouri, who issues his famous “Extermination Order” on October 27 to Militia General John Clark:

The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from

the state if necessary for the public peace—their outrages are beyond all description.

Two days later, the Haun’s Mill Massacre occurs, with 250 vigilantes attacking a Mormon camp, killing seventeen and pursuing the rest back to their base at Far West. Once there, Smith is forced to surrender. He is then tried on November 1 before a Military Tribunal and sentenced to death.

But General Alexander Doniphan refuses to carry out the order and Smith, along with other church leaders, are imprisoned for the next five months before his captors allow him to “escape” across the Mississippi River to Illinois, as good riddance. This banishment from Missouri ends the “Mormon War of 1838.”

Smith resettles his follower just east of the river in the small town of Commerce which he renames Nauvoo (“beautiful” in Hebrew). In addition to his role as head of the church he becomes Mayor and assumes control over all local affairs and the economy. Mormons dominate the town’s elections and the primary civic offices, in effect replacing traditional American democracy with their own brand of theocracy. These moves serve the Mormon population well and its numbers grow to around 12,000 by 1840. They also give Smith a chance to refine church dogma, including belief in “exaltation” for members and the call for “plural marriages,” ostensibly to rapidly expand the number of converts.

But in 1842 new controversies arise. They begin when the Mormon’s nemesis in Missouri, Governor Boggs is wounded by an unknown assailant and blames Smith for the attack. Boggs demands that he be extradited and tried for treason. Illinois Governor Thomas Ford has Smith arrested before his supporters finally force his release.

In response to the arrest, Smith goes on the offensive, demanding that Nauvoo be declared an Independent Territory, with its own Governor and the authority to call in U.S. troops to defend any threats to its citizens. At the same time, he announces his candidacy to run for President in the 1844 national election.

Then internal trouble brews once again, this time between Smith and other church leaders, notably William Law, a member of the “First Presidency.” Law accuses him of mishandling the economy and of implementing his policy of “plural marriages” to steal his wife. In response, Smith excommunicates Law, his spouse and several other dissenters.

Rather than departing quietly, however, they band together to form the “Mormon Seceders,” and publish a newspaper, The Nauvoo Expositor, on June 7, 1842. In it they accuse Smith of acting like a dictator and call for church reforms including a ban on polygamy.

From there events rapidly spin out of control. Smith calls for destruction of the newspaper presses and a Mormon mob carries that out on June 10. The Seceders protest in state court and an order to arrest Smith is issued. He declares martial law in Nauvoo and calls out his Legion militia to block the order. Illinois Governor Ford signals his intent to send in a full brigade to enforce the law, which convinces Smith to surrender, along with his brother, Hyrum.

On June 25, the two Smiths are imprisoned in a second floor cell of the two story brick jailhouse in Carthage, Illinois, 22 miles southeast of Nauvoo. Two days later an armed mob numbering upwards of sixty men storm the jail around 5:00pm. Their opening fire penetrates the jail door and strikes Hyrum in the face, killing him instantly. Joseph returns fire with a pepper-box pistol smuggled into him by a friend, wounding three assailants before he is shot dead as he falls from the window to the ground below. Five people are subsequently tried for the attack, but all are acquitted.

The aftermath of the murder finds Brigham Young, a member of the ruling “Quorum of Twelve,” winning out over Sidney Rigdon for leadership of the Mormons. Young recognizes that an exit from Nauvoo is necessary and sets out west in February 1865 with a vanguard of 1600 men, women and children. Those who remain behind are met with further local violence and most eventually leave.

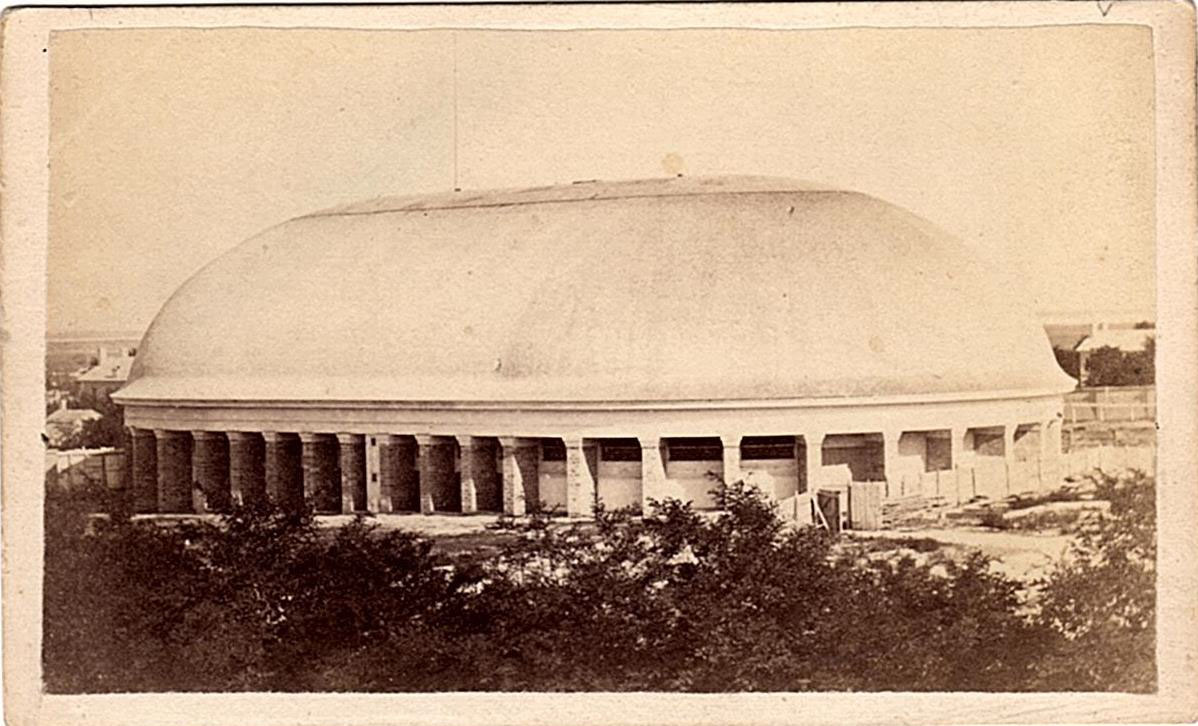

After a seventeen month trek, Young’s initial pioneers reach Salt Lake City, Utah. He christens the land as the “Theocratic State of Deseret” and the final site for the new Zion. Census data peg the population size of Salt Lake City at 6,175 in 1850 and 11,314 in 1860. The residents there begin to build their Tabernacle in 1853, a project not fully completed until 1875.

While the Mormons will become the lasting dominant force in Utah, they face many of the same challenges encountered in Kirtland and Nauvoo, including the arrival of federal troops in 1857 to resist their wish for independent nation status. Instead Utah is admitted as the nation’s 45th state in 1896.

To this day Smith’s body is buried side by side with his brother Hyrum in Nauvoo, along with his wife Emma who becomes one of the few Mormons who remain in the town after the tragedy. She dies in 1879, denying to the end that Joseph ever fostered polygamy:

No such thing as polygamy, or spiritual wifery, was taught, publicly or privately,

before my husband’s death, that I have now, or ever had any knowledge of ….

He had no other wife but me; nor did he to my knowledge ever have.