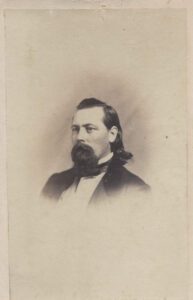

Ward Lamon, Lincoln’s Bodyguard

At 6’4” tall, 260 pounds and armed with brass knuckles, a blackjack and a Bowie knife, the man known as Hill Lamon (pronounced “Lemon””) is every inch a credible bodyguard for Abraham Lincoln. His devotion to the job finds him side by side with the President during the day and, at night, patrolling the grounds of the White House or, as reported by secretary John Hay, “wrapped in his cloak and lying down to sleep in front of Lincoln’s bedroom door.”

Beyond that, however, Lamon – who is twenty years younger than Lincoln becomes a trusted companion and friend to a President often in need of refuge from the daily tensions of his office. He possesses the youth and upbeat personality capable of lifting Lincoln out of the frequent bouts of melancholia he calls “the Hypo.” When a ribald joke is required, Lamon delivers it, often lubricated by a jar of whiskey. Or perhaps a lively and talented rendition of “Blue Tail Fly,” one of the President’s foot-stomping favorites.

The two don’t meet until “Hill,” who is born in Virginia, moves to Danville, Illinois, passes the bar in 1851 at twenty-three, and begins to practice law. By then, Lincoln is already well established and he takes Lamon under his wing on various circuit court cases. This continues until 1856 when Hill is elected as Public Prosecutor of the 8th Judicial District in Bloomington. But the bond remains and Lamon campaigns vigorously in Lincoln’s 1858 Senate race and his 1860 presidential victory. While hoping for a diplomatic posting, Lincoln tells Lamon that “he needs him” in Washington, and names him U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia.

In a famous early “protector” incident Lincoln later regrets, Lamon sneaks the new President-elect into DC in a disguise in response to assassination threats at his stop-over in Baltimore. Here, as in events going forward, Lincoln is convinced that he is in no danger whatsoever.

As war tensions rise, Lamon is sent to Ft. Sumter where he figures out how to meet with the besieged Colonel Robert Anderson by telling South Carolina Governor Pickens that he is there to arrange evacuation of the site. Once the actual fighting begins, Lamon briefly organizes a brigade of anti-secession Virginians, before returning to the White House for the duration.

On November 19, 1863 he is given the honor of introducing Lincoln at the dedication of the new cemetery at Gettysburg. Afterwards he reports the President’s unfounded dismay with the immortal three minute speech: “it won’t scour.”

The end of the war brings the tragic assassination at Ford’s Theater, with Lamon away in Richmond, having been sent there by Lincoln to Richmond to assess Virginia’s re-entry into the Union. In his place that night is DC policeman John Parker who leaves Lincoln alone at the first intermission and is sitting in the Star Saloon next door when Booth strikes. Parker is charged with neglect of duty before admitting his guilt and escaping punishment.

Several years later Lamon decides to offer his own biography of the President. He pays $4,000 to Willie Herndon, Lincoln’s former law partner, for his collection of source document interviews done with early friends and neighbors covering the Springfield days to the start of the presidency. Lamon then hires Chauncey Black, son of Buchanan’s AG, to ghostwrite the book. It is a rambling series of recollections, cast in the language of everyday people, which portrays a flesh and blood version of Lincoln from youth to manhood. But at a time when other authors are elevating him to sainthood, Lamon’s book is roundly criticized for revealing imperfections about his temper, his religious beliefs, his off-color tunes, his braggadocio:

- He bit off the nose of Abraham Enlow in a fight;

- Used a bludgeon on resistant Negroes in New Orleans;

- Wrote that the Bible was not God’s revelations;

- And that Jesus was not the Son of God;

- Talked about his depression and suicide;

- Favored bawdy songs: “Hail Columbia, happy land, if you ain’t drunk I’ll be damned;”

- Bragged early on about one day becoming President.

Lamon’s book sells only 2,000 copies in 1872; critics call it “vulgar;” and Lincoln’s son Robert uses his DC clout to block Hill’s future government aspirations. His wife, Sally, dies in 1892 and he follows her a year later at age sixty-five.