February 13, 1819: The Tallmadge Amendment rings like “a fire bell in the night” for ex-President Jefferson.

James Tallmadge, Jr. is a 41 year old graduate of Brown University, a lawyer, ex-soldier in the War of 1812 and serving his one term in Congress when he becomes famous for offering an amendment to a bill to admit Missouri as the 23rd state in the Union. It supports the addition, but only…

Provided, that the further introduction of slavery…be prohibited…and that all children born within the said State after the admission thereof into the Union shall be free, but may be held to service until the age of twenty-five years.

In one fell swoop, this threat to the expansion of slavery by Tallmadge picks the scab off the sectional wounds that threatened in 1787 to derail the effort to arrive at a national Constitution and Union. The heated exchanges which follow remind many present of those at Philadelphia between Gouvernor Morris, the ardently anti-slavery delegate from Pennsylvania, and his pro-slavery antagonist James Rutledge of South Carolina.

The Tallmadge Amendment lets the slavery genie out of the bottle, and for the next four decades future members of Congress will be left to struggle with this fact.

Two founding fathers weigh in on the debate. In a letter to his wife, John Adams comments:

Negro Slavery is an evil of Colossal magnitude and I am utterly averse to the admission of Slavery into the Missouri Territories.

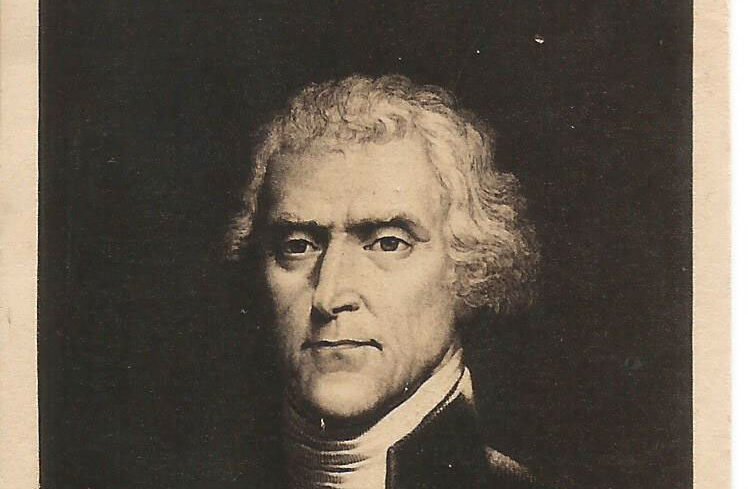

Meanwhile, from his peaceful mountaintop in Monticello, the 76 year old Thomas Jefferson, recognizes the import of the Tallmadge Amendment:

This momentous question, like a fire bell in the night, awakened and filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union.

Henry Clay’s 1829 Missouri Compromise defuses the crisis by admitting the Free State of Maine along with Missouri and establishing a 36’30’ boundary line on slavery in the Louisiana lands.