The origins of rice in America, the Gullah people and William Aiken Jr.

Before William Aiken Jr. enters the picture it’s necessary to tell how the Gullah people introduced rice to America. When captive west coast Africans land in Charleston around 1650 they arrive with a host of different local traditions and speaking a variety of different tongues. Then, in order to survive their enslavement, they gradually form a unique culture that becomes known as Gullah or Geechie, with its own language, traditions, crafts, music, and cuisine.

The Gullah language is “creole,” a mish-mash of various African dialects and Pidgin English forever mysterious to the colonists. Over time, many Gullahs convert to Christianity, while retaining their African rituals in “ring shouts,” with congregants dancing in a circle, chanting, and beating sticks together to set the rhythm. A belief in witchcraft also endures, with cabin doors painted sky blue to trick “haints” (evil ghosts) into passing them by. Their music includes spirituals and anticipates ragtime, soul forms and jazz. Elders no longer able to do hard labor spend their time weaving carry baskets from sawgrass.

But it is the Gullah cuisine that has an important effect on the agricultural destiny of the South. Its foundation is rice, and the Africans are well versed in the complex steps required to plant and harvest it.

Success depends first on access to vast swampland, fed by non-saline freshwater rivers and lakes, where temperatures are reliably warm during the 5-6 month growing season. South Carolina in particular is an ideal fit. Then comes the know-how to prepare and manage a rice field, first to drain and level the swamp, then to plant seedlings in the mud, and to carefully add back water needed to support growth and fight off weeds. Finally, between April and September, stalks reach about 18 inches, at which time they are cut down, left to dry in the sun for two weeks, then “flailed” to capture pods and milled to arrive at the desired rice kernels.

The value of Rice exports reaches $ 2.3 million, third place behind the other cash crops of cotton and tobacco

The entire process is fraught with risks. Inland swamps are subject to flooding after heavy rains, while coastal swamps are forever threatened by the ocean’s salt water. Losing a crop to water damage is not uncommon and severe financial losses can follow. Swampland is also the breeding ground for mosquitos and the two main killing diseases they transmit – malaria and yellow fever. But the Gullah’s resistance to both has increased over years of laboring in shallow water under a blazing sun.

Still, by 1650, the Gullah people have taught the plantation owners to produce the Carolina Gold brand of rice that becomes a staple in the colonist’s diets. Two hundred years later, around 1850, the value of Rice exports reaches $ 2.3 million, third place behind the other cash crops of cotton and tobacco. South Carolina accounts for roughly 80% of this volume.

Estimated Value Per Year for Exports ($000)

| Year | Cotton | Tobacco | Rice | Sugar |

| 1840 – 50 | $ 55,314 | $ 8,166 | $2,359 | $314 |

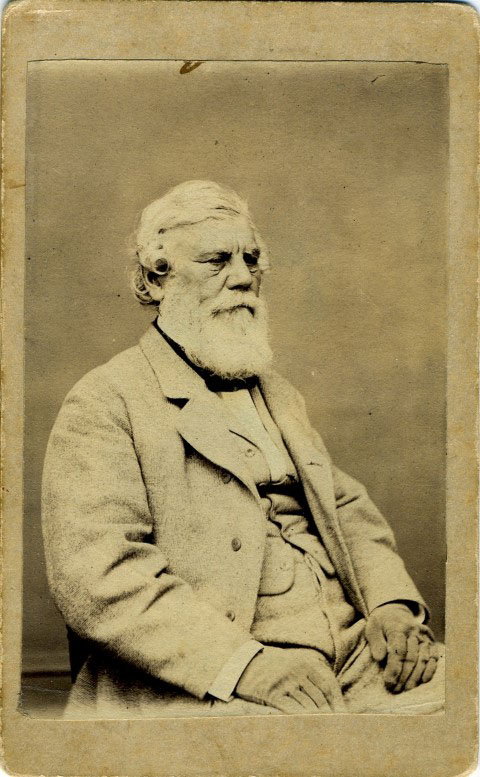

Within the rice sector, the most advanced plantation belongs to William Aiken, Jr. and is located on Jehossee Island, thirty miles south of Charleston. Aiken is 25 years old in 1833 when he acquires the property with wealth inherited after his railroad tycoon father is killed in a carriage accident. Production is concentrated on 1500 acres with an elaborate system of rice trunks and tidal irrigation dikes built and worked by some 700 “Gullah” people. The operation is vertically integrated all the way to pounding mills for economies of scale.

By all accounts, Aiken is regarded as a kind overseer. A New York journalist reports that “he is more concerned about making his people comfortable and happy than about making money.” True or false, Aiken is well respected in the state and in 1837 he enters politics, which culminates in his election as Governor in 1844. From there he is off to Washington, serving four terms as a Democrat in the House from 1853-57. Aiken is strongly pro-state’s rights, but also a Union man. When the time comes, he refuses to sign his state’s secession petition.

While the war takes its toll on both Aiken and Jehosee Island, the Gullah culture, the muscle, and soul of the plantation, survives to the present day. In the marketplace stalls of Charleston, seated women weaving their sweetgrass baskets, the smell of jambalaya and red rice and okra soup simmering, the sing-song sounds of Geechie, a mysterious sense of long-ago bonds, of bright sun, stinging whips, of coded reassuring shouts and mysterious herbal cures, hags casting spells over the Man, and of never-ending rows of wild African rice to harvest on a foreign shore, dreaming of home.

Learn more about The South’s First Cash Crops: Tobacco, Rice, Cotton, And Sugar

Learn more about The Southern Planter Tycoons