Reverend James Henley Thornwell Slavery A Positive Good

With slavery established in all 13 colonies by 1700, debates about its morality begin to surface, especially among the clergy. At the time, the fundamentalist ministers who dominate America’s early churches preach that the literal words of the Bible are both correct and unerring. They cite the Old Testament book of Genesis and the “curse of Ham” to verify the ancient roots of slavery – and then argue that Christ never condemns the practice in the New Testament. For them, and for their flocks, the Bible “proves” that slavery must not be considered a sin.

That view prevails into the 19th century even with Northern church leaders such as Vermont Bishop John Hopkins and Rev. Charles Hodge, Principal of the Princeton Theological Seminary.

Thornwell focuses on a newer angle, contrasting the life of those enslaved on Southern plantations with Northerners dependent on factories and sweatshops for survival

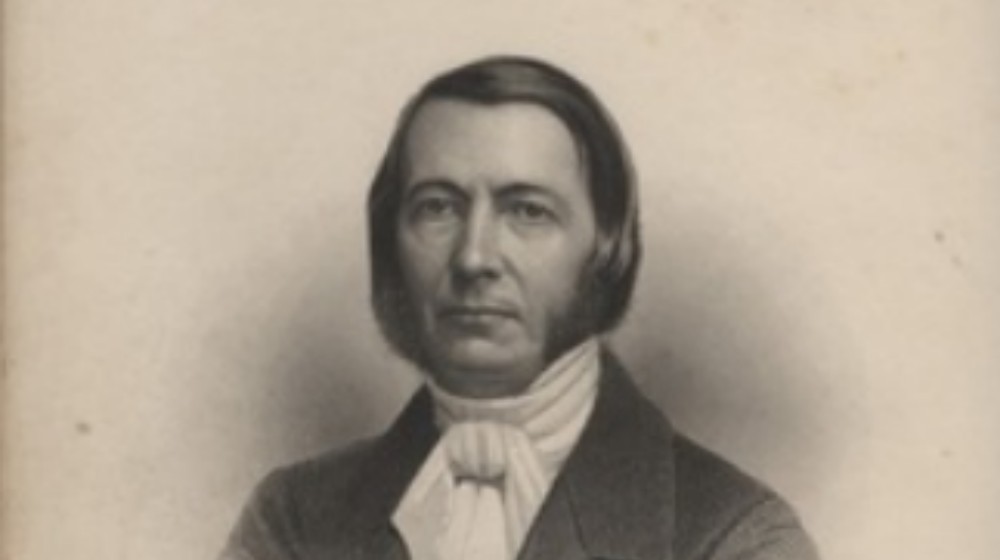

However, as the anti-slavery movement gains momentum in the 1840’s, Southerners who fear that chaos would follow from emancipation, go on the offensive to protect the status quo. One clerical spokesperson they rely on here is the Reverend James Henley Thornwell.

Thornwell is born in 1812 on a plantation where his father acts as overseer until his death in 1820. Friends pay for his education including South Carolina College, where he graduates first in his class in 1831. Stints at Andover and Harvard follow before he is ordained a Pastor in the Presbyterian Church. His main calling, however, lies in biblical scholarship, and in 1855 he is named Professor of Theology at Columbia Theological Seminary. As the Civil War approaches, Thornwell emerges as champion of the South’s assertion that “slavery is a positive good.”

While he unabashedly owns slaves, Thornwell preaches that paternalism and “loving Christian precepts” must be applied to their care. At the same time, his defense of slavery echoes that of two other South Carolina men: James Hammond and John C. Calhoun. In 1836, Hammond espouses his “Mudsill Theory,” claiming that successful societies throughout history have relied on an enslaved class to handle mundane tasks while freeing up “superior men” to govern and advance the culture. Calhoun reiterates this belief in his 1837 speech to the Senate:

I hold that, in the present state of civilization, where two races of different origin,

and distinguished by colour, and other physical differences, as well as intellectual,

are brought together, the relation now existing in the slaveholding states between

the two is, instead of an evil, a good — a positive good.

After Calhoun dies in 1850 the mantle falls on Thornwell to go on the offense against those supporting abolition. His theological arguments rely on the usual Biblical references and the assertion that captivity has opened a path to eternal salvation for the Africans. But on top of this he focuses on a newer angle, contrasting the life of those enslaved on Southern plantations with Northerners dependent on factories and sweatshops for survival. He asks “who is better off” in terms of lifetime guarantees of shelter, food, medical care and support in old age? In this defense of slavery, Thornwell joins other contemporary intellectuals such as Marx in attacking industrial capitalism.

Until the war breaks out Thornwell favors a compromise to save the Union. But then he sides whole heartedly with the Confederacy until his death at forty-nine from tuberculosis in 1862.

Learn more about James Henley Thornwell