February 24, 1803: The Marbury v Madison ruling defines the authority of the Supreme Court.

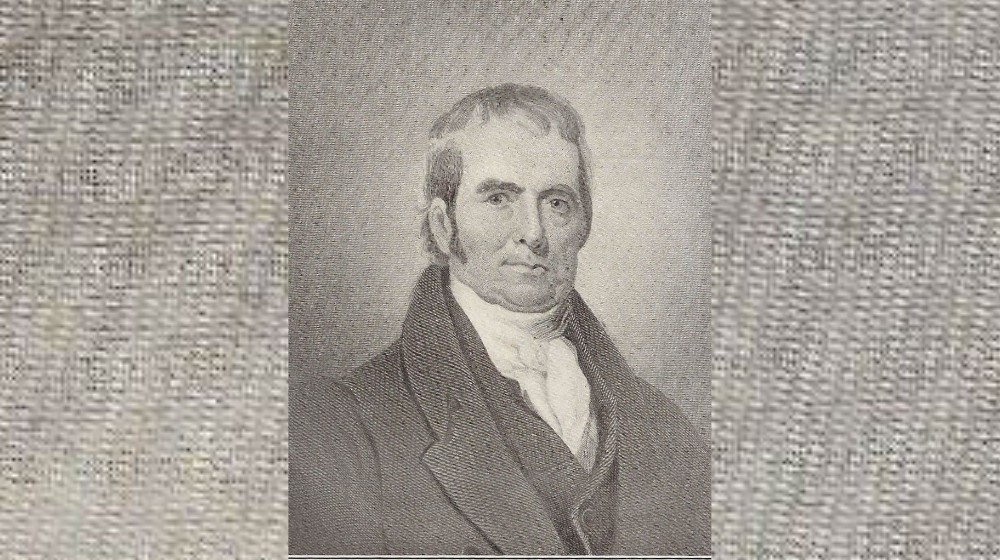

Fifteen years after the founding fathers create the judicial branch of the federal government, the nation’s fourth Chief Justice, John Marshall, defines the authority of the Supreme Court over the laws of the land in his Marbury v Madison decision.

Until that moment the High Court has floundered under three prior Chiefs, unsure of its role and with so little impact that two resign from their lifetime appointments. This changes with Marshall who serves for 34.5 years and literally transforms the court into the third co-equal branch of government.

While Marshall is a second cousin of Thomas Jefferson, his mother is shunned by Tidewater society for marrying below her station. He grows up in a log cabin, fights in the Revolutionary War, then apprentices in the law before being elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses as a conservative. He is 45 years old when President John Adams names him Chief, hoping that he will offset the policies and power of Jefferson and the anti-Federalists.

Marshall’s Court is hardly settled in when it confronts a case brought by William Marbury, a Georgetown businessman and Federalist supporter, who has been offered a post as Justice of the Peace for the District of Columbia by Adams. But once in office, Jefferson orders his Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold delivery of his official commission. Marbury responds by filing a writ of mandamus, citing the Judiciary Act of 1789 and asking the Supreme Court to force Madison’s hand.

Marshall recognizes the potential here for a direct confrontation between the Judicial and Executive branches and the possibility that Jefferson will simply ignore the Court’s decision if it goes against him. To settle the matter, and also defuse the conflict, Marshall issues his landmark ruling. It says that while the Justices find the plaintiff deserving of the commission, it has no legal jurisdiction to rule on the matter because Section 13 of the Judiciary Act conflicts with the language in Article III of the U.S. Constitution.

In other words, the Court cannot force Madison to comply because a part of the 1789 Act is unconstitutional and must be struck down. The net effect of this outcome is three-fold:

* By concluding that Marbury deserved a commission, the Court slaps Jefferson on the

wrist for denying it;

* By not trying to force issuance of the commission, the Court denies Jefferson a chance

to ignore the order, and hence reject its authority; and

* By stating that Section 13 of the 1789 Act is unconstitutional and must be struck down,

the Court affirms its power of “judicial review” over the nation’s federal and state laws.

As Marshall says, “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” And most judicial historians regard Marbury v Madison as the most significant ruling in constitutional history. It fails to hand Marbury the post he deserves, but does forever establish the power of the Supreme Court to make the final calls on all bills passed by the legislative branch.