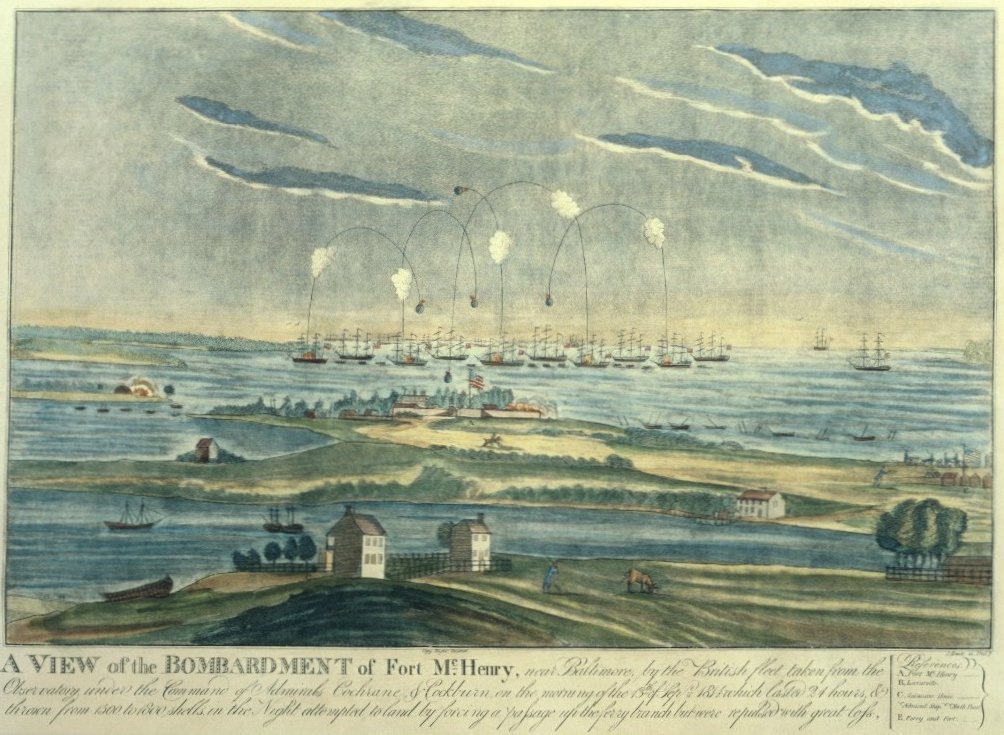

September 14, 1814: Ft. McHenry

You are there: The Atlantic coast phase in America’s second war for independence from Britain better known as the War of 1812, comes to an end with the successful defense of Ft. McHenry in Baltimore harbor.

Battle of Lundy Lane

On July 25, 1814, the bloodiest single battle of the war takes place at Lundy’s Lane, two miles west of Niagara Falls. When it ends in a draw, fighting along the Canadian border is over, and Britain shifts its focus to assaults along the Atlantic coast.

Reinforcements from Europe

The Royal Navy has already formed a stranglehold blockade there, and with Napoleon now in exile at Alba, Britain sends infantry reinforcements to invade inland.

Their leader is the Dublin born Major General, Robert Ross, who has fought valiantly alongside Wellington, and is now given command over all army troops. Along with his naval counterpart, Vice Admiral George Cockburn, Ross plans a two-pronged assault aimed at his opponent’s heart, the capital city of Washington.

The plan involves a naval flotilla consisting of 4 ships-of-the-line and 20 more frigates and war sloops, under Admiral Alexander Cochrane, along with amphibious landing crafts to carry Ross and his 4,400 men, mostly veteran Royal Marines.

Landing at Benedict

On August 19, Ross disembarks at Benedict, Md. and begins marching northwest toward the town of Bladensburg, about 10 miles above Washington, on the east branch of the Potomac River. Once there they encounter an American force consisting of 6500 Maryland militia and 400 U.S. Regulars under Brigadier General William Winder.

Battle of Bladensburg

The August 24, 1814 Battle of Bladensburg proves to be one of the greatest routs in American military history. Winder has aligned his troops poorly and they are decisively thrashed by Ross. Lacking any pre-planned line of retreat, the U.S. forces turn tail and dash for Washington, DC, 10 miles to the southwest. This flight, which includes both President Madison and Secretary of State Monroe, is immortalized as “The Bladensburg Races” in a satiric British poem in 1816.

Away went Madison, away Monroe went at his heels,

And all the while his laboring back, a merry thumping feels.

The Capitol Burns

But the worst is yet to come on this day at Washington City. Secretary of War Armstrong is certain that the British will never reach the capital, and has made essentially no preparations to defend it. Ross’s troops arrive in the capital by evening on the 24th and are shot at when they approach under a truce flag. This leads to a 26 hour rampage in which the Capitol, the White House and the US Treasury are all pillaged and burned – in return, the British claim, for similar destruction of their provincial capital of York in April, 1813.

With the US government stunned and momentarily homeless, Ross and his troops exit Washington to rejoin Admiral Cochrane’s flotilla on August 26th and take aim at their second objective, capturing the critical port city of Baltimore.

General Ross is Killed

On September 12, Ross disembarks at the town of North Port, on Chesapeake Bay, twelve miles southeast of Baltimore. But now the Americans are ready for him. General John Stricker has laid out a strong defensive position at North Port. These include redoubts around the city, marked by tidal swamps and creeks that force the British to funnel through a narrow strip of land, where his 3200 Maryland militia men wait in ambush. While the battle ends after two hours with the Americans withdrawing, the British suffer a crucial loss when General Ross is mortally wounded by a musket round that strikes him in his right side.

Battle of Baltimore

On September 13, the Battle of Baltimore hangs in the balance.

The now 5,000-strong British ground troops, under Colonel Arthur Brooke, encounter very stiff resistance at Hampstead Hill from what has grown to be 11,000 militiamen, led by Generals Stricker and Winder. At 3AM, Brooke concludes that the initiative is lost, and begins to withdraw his men.

Meanwhile the Royal Navy approaches Ft. McHenry at the entrance to Baltimore harbor. It is built originally in 1776, during the Revolutionary War, and named Ft. Whetstone. But it’s then completely overhauled in 1798 by Frenchman Jean Foncin who chooses its unique 5-star shape designed to more readily deflect incoming naval shells and to provide better fields of fire against ground troops. Once completed, it is named after James McHenry, a signer of the 1787 Constitution who serves as Secretary of War under Washington and Adams.

Admiral Cochrane makes one close pass at the fort before being driven away by the American’s cannon. He then backs off some two miles beyond their range, and for the next 25 hours rains some 1500 shells down on the defenders. But, almost miraculously, only one man is wounded and, when the sun rises on September 14, the American flag appears on the ramparts signaling reveille as usual.

Star Spangled Banner

In the harbor, a 35 year old American lawyer named Francis Scott Key, on board a British ship to conduct a goodwill mission for President Madison, watches the bombardment through the rainy night, wondering what the morning of September 14 will bring. At dawn, he glimpses the Stars and Stripes and immortalizes the sight forever in his poem, The Star Spangled Banner.

At this point the British commanders call off the assault. On the water, they have been unable to put the cannons at Ft. Henry out of action. On land, their troops have been decisively turned back by the American’s entrenchment works. So off they sail with Admiral Cochrane making a final appearance at the battle of New Orleans.