June 18, 1815: The Napoleonic Wars End With The French Defeat At Waterloo.

You are there: Nearly twenty years after Napoleon’s France uses its military might to achieve global dominance, its days of glory come to an end in Belgium at the Battle of Waterloo.

A Corsican by birth, Napoleon’s meteoric rise in his adopted country begins in 1793, four years after King Louis XVI is guillotined, when he puts down a rebellion by Royalist and Anglo forces at the port city of Toulon. Two years later he achieves political power as First Counsel of the Republic after conquests in Italy, Egypt and Syria. In 1805 he responds to Britain’s declaration of war by crowning himself Emperor and embarking on campaigns to crush the continental monarchies and their colonial possessions.

Following a momentary naval setback at Trafalgar, he scores stunning victories at Austerlitz over Russia and the Holy Roman Empire and at Jena-Auerstadt over the Prussians. Casualties at these two battles alone top 86,000 soldiers. In 1809 he defeats Portugal, Spain and an Austrian-British Coalition. By 1811 France sits astride its opponents with clear-cut hegemony around the world. But then comes 1812 and a fatal decision to drive inland in Russia to capture Moscow.

On July 24, 1812 Napoleon’s 400,000 man army crosses the Nieman River and begins a 600 mile march to the east. Just over four months later some 30,000 return after suffering 270,000 casualties to battle losses and a devastating bout of typhus, with another 100,000 captured. Napoleon has lost Russia at Borodino and Moscow, along with his mantle of invincibility.

His enemies now form the 6th Coalition to retake the continent. After brilliant French comebacks at the battles of Lutzen, Bautzen and Dresden, allied forces under the British General Wellesley (later Duke of Wellington) conquer Spain. Then comes the decisive loss to a combined force of Austrians, Prussians and Swedes at the Leipzig, the largest battle in history up to the World War I attack on the Somme in 1916.

The French capital finally falls to the coalition in March 1814, followed by the May 30 Treaty of Paris ending the Napoleonic Wars. Under the terms, King Louis XVIII is restored to the throne and Napoleon is not executed but rather banished to the island of Elba just off the southern coast of France. But he remains there for only 300 days before returning to Paris on March 19, 1815, with 600 troops, as King Louis flees and the people flock to his banner.

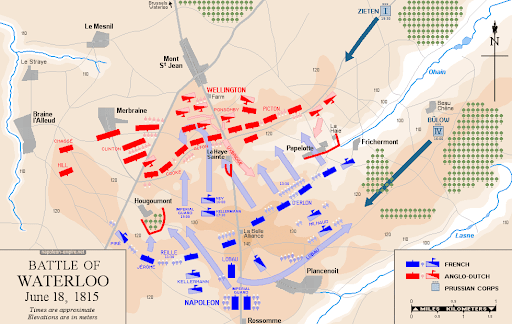

The period which follows, known as “The Hundred Days,” finds Napoleon on the offensive with a veteran army of 70,000 and his eyes set on taking Brussels. He approaches from the south, arriving on June 18 below a ridge running east and west for 2.5 miles in front of the town of Mont St. Jean. Along the ridge are British troops under Wellesley, arrayed in a strong defensive posture to grind down any frontal assault on the center. His flanks are also covered, on the right by the farmhouse Chateau Hougoumont and on the left at La Haye Sainte and Papelotte. Wellesley has decided to make a stand after hearing that Prussian troops under Generals Blucher and von Bulow are on their way to reinforce him.

Napoleon rises at 8AM, takes breakfast, and rides north to review his troop alignments – his light infantry chasseurs in bright green, the light cavalry hussars, mounted cavalry dragoons and carabineers with long guns strapped to saddles, cuirassiers wearing metal breastplates, the towering grenadiers, chosen to lead assaults, in their blue and scarlet uniforms and bearskin headgear designed to add to their natural height, the cavalry lancers with their 10 foot wooden staffs tipped by a sharp steel blade, and the artillerymen, “his most beautiful daughters,” whose mastery and courage have won him many a victory.

But Napoleon is in no rush to attack. It has rained all night on the 17th, and the field of rye across which the French will make their assault is muddy and slippery. So he waits until 11:30AM, at which time he makes his first move of the day – against the crucial fortifications on his left at Hougoumont. If the Chateau falls, his canoners can ascend the ridge on the left, send enfilading fire down the entire British line, and claim a certain victory.

Artillery fire announces the French move, and it is quickly returned in kind: 4-12 pound solid iron balls bouncing along the ground and gouging body parts, sometimes 15-20 soldiers at a time, before being spent. Next comes the infantry, marching in order up the slope to the Chateau. The hand to hand fight there lasts for 90 minutes, the only action on the field.

When Hougoumont holds out, Napoleon next tries the British right, a heavy artillery barrage followed by massed infantry, 24 columns deep, coming up east of the Brussels road and past the fortified buildings of La Haye Sainte. Again the defenders drive the French back, led by a heroic cavalry charge behind Sir Thomas Picton, who is mortally wounded.

It is now 3PM and a pause leads many to think the battle is over. While the Duke is constantly visible along the ridge, Napoleon remains slouched in a field chair 1.5 miles back from the action, sending few orders and trusting Marshall Ney to manage the tactics. Amazingly the two do not meet face to face from 9AM until 7PM.

Around 4:00PM, Ney, evidently on his own, decides to test the British center. He does so in highly irregular fashion, using cavalry alone, unsupported by infantry.

Wellington responds by “forming squares,” the traditional defense against cavalry. The goal here is first to discourage the horses via planted pikes, and then to shoot them – leaving their armor clad riders stumbling on the field. And this strategy succeeds. Some 12,000 French cavalrymen ascend the slope in magnificent order, only to be broken up into mingling clusters by the square’s concentrated firepower. By some estimates they re-form on twelve occasions to charge again and be rebuffed.

By 4:30PM Wellington, stationed openly in one of the squares, tells an aide “the battle is mine, and if the Prussians arrive soon, there will be an end to the war.” But when the French finally take La Haye Sainte, his confidence lessens – and the outcomes again hangs in the balance. Wellington has now shot his bolt, his troops are fought out, and his hope for survival rests on the appearance of von Bulow’s Prussians to plug his gaps.

This is Napoleon’s last best chance. He has held 14 regiments of his best troops, The Imperiale Garde, in reserve to the south. But when Ney requests them, Napoleon refuses to comply.

It is 7:00PM and the Emperor now knows that the Prussians are attacking his right flank, through Papelotte and, further south, at Plancenoit.

His options are running out. Does he use his reserves to hold off the Prussians or fling them up toward the British on the ridge? At 7:30PM he chooses the latter course. He mounts his horse and leads five regiments of his Imperiale Garde north to the battle. The Garde, the “Immortals,” famed for their courage – “the Garde dies, it does not retreat.”

Many expect Napoleon himself to ride at the front of his troops, but he turns them over to Ney who has already had five horses shot from under him and is near exhaustion. Instead of taking the Brussels road up to the ridge, Ney veers left across the same ground as his prior cavalry charge. This adds 1,000 yards to the task, with the remains of the British artillery firing away.

As the Garde reaches the apparently accessible ridge, some 1,000 British infantrymen, the 1st Foot, under the command of Major General Peregrine Maitland, rise as if from nowhere, and shoot them down. And the Garde turns and flees back down the slope.

At this moment, the French have indeed lost the battle. Wellesley waves forward his troops, just as the Prussians break through from the east.

Napoleon rallies the remnants of the Imperiale Garde, south at La Belle Alliance along the Brussels road, and enables his troops to exit the field toward the south and west.

Around 9:30PM Wellesley and Blucher meet up on the southern part of the field to seal their victory. Britain has lost 15,000 killed and wounded; Prussia another 7,000. Napoleon has lost 15,000 men – and his empire.

As the Coalition army closes again on Paris on June 24, Napoleon abdicates. He surrenders personally on July 22 to the British, seeking “hospitality and the full protection of their laws.”

According to the traditions of the age, Napoleon again suffers banishment not execution, this time to the Island of St. Helena, one of the most isolated in the world, off southwestern Africa. He lives there until his death in 1821, presumably of stomach cancer. In 1840 his remains were shipped back to Paris, where he lies in Les Invalides. Le jour de gloire has come and gone – for Napoleon and for revolutionary France.

le jour de gloire s’en est allé” — the day of glory has vanished