Section #15 - Northerners rebel after the 1854 Kansas- Nebraska Bill reneges on the Compromise of 1820

Chapter 179: Congress Passes The Controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act

December 6, 1853

Pierce Sends His First Annual Message To Congress

With Gadsden primed for a successful visit to Mexico City, the 33rd Congress convenes for its initial session on December 5, 1853. The next day, President Pierce’s first annual message is read into the record.

It begins on a somber note, remembering those recently dead (some 8,000 in New Orleans alone) from the mosquito borne viral infection known as yellow fever, and invoking his “abiding sense of dependence upon Him who holds in His hands the destiny of men and of nations.”

While he states that foreign affairs have “undergone no essential changes,” he calls out several noteworthy issues and events:

- Agreements with Britain over fishing rights in the northeast and boundaries in the northwest.

- Concerns over “unauthorized expeditions” against Cuba and Porto Rico.

- The “justifiable conduct” releasing citizen-to-be Martin Koszta from illegal seizure by Austria.

- Commodore Perry’s return to Japan in search of opening trade.

- Attempts currently under way to resolve border disputes between the U.S. and Mexico.

- A full litany of initiatives to open relations and trade across Central and South America.

Likewise on the domestic front, comes a very long and detailed accounting:

- The nation’s finances are in good shape, with revenues exceeding the needs of government.

- A plan is forthcoming to reduce tariff rates on many items.

- Surveying has now been completed on almost 10 million acres of new public land.

- Some 335,000 acres of land have been sold recently for a total of $625,000.

- Both the Navy and the Army “require augmentation.”

- The judicial system needs to be modified and enlarged.

- DC will enjoy an improved water supply, a new insane asylum, the Smithsonian Institution

- The Post Office is facing “enormous rates” from railroads to carry mail.

A high priority within his domestic agenda is progress toward a transcontinental railroad. It will provide “the means of communication by which the different parts of our country are to be placed in closer connection for purposes of both defense and commercial intercourse.” Work is already under way to:

Ascertain the most practicable and economical route for a railroad from the river Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean.

While oversight on this transcontinental railroad belongs with the government, Pierce assures Congress that the actual construction work and costs will be borne by private corporations and their investors.

The General Government to undertake to administer the affairs of a railroad, a canal, or other similar construction, (but) its connection with a work of this character should be incidental rather than primary.

Taken together, the bulk of Pierce’s address paints the picture of an America that is sailing along smoothly in January, 1853, under the leadership of a still new president who has quickly mastered his role and is proceeding with confidence.

But scattered throughout the speech are snippets that suggest a different reality – one filled with “anxious apprehension” and “disturbing questions.” Pierce scrupulously avoids the word “slavery” here, but those in his congressional audience and in the press can easily fill in the blanks.

The year 1850 will be referred to as a period filled with anxious apprehension. A successful war had just terminated. Peace brought with it a vast augmentation of territory. Disturbing questions arose bearing upon the domestic institutions of one portion of the Confederacy and involving the constitutional rights of the States.

Beyond that, comes nothing but “wishful thinking” on his part.

Even though he knows full well that the 1850 Compromise has not resolved the “disturbing questions,” he asserts that “the controversies are passing away” and that a “new league of amity and mutual confidence” has dawned which will result in “domestic peace.”

The controversies which have agitated the country heretofore are passing away with the causes which produced them and the passions which they had awakened; or, if any trace of them remains, it may be reasonably hoped that it will only be perceived in the zealous rivalry of all good citizens to testify their respect for the rights of the States, their devotion to the Union, and their common determination that each one of the States, its institutions, its welfare, and its domestic peace, shall be held alike secure under the sacred aegis of the Constitution.

This new league of amity and of mutual confidence and support into which the people of the Republic have entered happily affords inducement and opportunity for the adoption of a more comprehensive and unembarrassed line of policy and action as to the great material interests of the country, whether regarded in themselves or in connection with the powers of the civilized world.

The outlook, he says, is for a “restored sense of repose and security for the public mind.”

But notwithstanding differences of opinion and sentiment which then existed in relation to details and specific provisions, the acquiescence of distinguished citizens, whose devotion to the Union can never be doubted, has given renewed vigor to our institutions and restored a sense of repose and security to the public mind throughout the Confederacy.

And that “this repose will suffer no shock” during his term in office.

That this repose is to suffer no shock during my official term, if I have power to avert it, those who placed me here may be assured.

Events, however, will soon prove that his assurances are misplaced.

Pierce’s speech ends as it begins, announcing another national loss, the passing of his Vice President, William King of Alabama, who succumbs to tuberculosis at sixty-seven, only six weeks after being sworn in. He will not be replaced, which means that the President Pro Tempore of the Senate would succeed Pierce if need be.

January 10, 1854

Douglas Offers His First Bill To Organize The Nebraska Territory

Now back from his five month long European tour, Stephen Douglas returns to the Senate eager to resume his crusade on behalf of opening the Nebraska Territory.

He finds that the power structure in Congress, like the population, is drifting toward the west. David Atchison of Missouri is chosen as President Pro Tem in the Senate and Kentucky’s Lin Boyd succeeds Howell Cobb as Speaker of the House. The important Committee on Territories in the upper chamber is expanded to six men, still headed by Douglas. He is joined by John Bell of Tennessee, the Texan, Sam Houston, Robert Johnson of Arkansas, Iowa’s George Jones, and the lone easterner and Whig, former Secretary of State, Edward Everett, of Massachusetts. This group will differ from start to finish in regard to the Nebraska Bill.

All six agree, however, that something must be done about the final “Unorganized Territory” remaining from the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Settlers are moving onto the land; a host of Indian tribes are already there; and the wish for a transcontinental railroad adds to the need to convert the Territory into a State.

Iowa Senator Augustus Dodge takes the lead here by announcing his intent to re-introduce the Nebraska Bill, which was tabled by a vote of 23-17 nine months ago on the final day of the 32nd Congress.

This Bill, like its predecessor, is crafted by Douglas; in fact he claims to have written it all by himself:

It was written by myself at my own house with no man present.

Since 1845, during the Texas Annexation debate, Douglas has witnessed his Bill go down to defeat time after time, and he vows to drive it through in 1854 by his personal force of will – and by “adjustments” aimed at gaining the Southern support he needs.

What continues to trouble the South is the prospect that Nebraska will become the “next California” – one more addition to the Free State majority in the Senate that can threaten the institution of slavery at any moment.

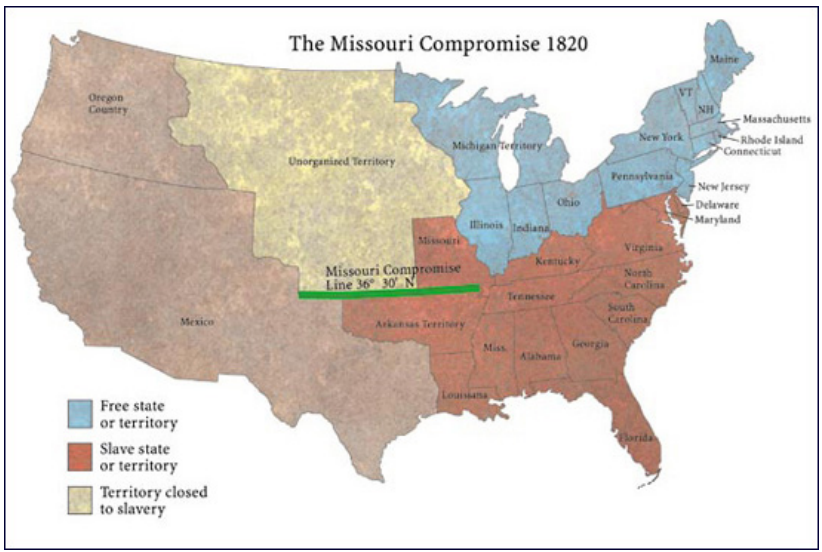

The Free State designation is “assumed” since the entire Nebraska Territory falls above the 36’30” boundary line on slavery, agreed to in the 1820 Missouri Compromise and applicable ever since to all land from the Louisiana Purchase.

In practical terms, Douglas finds this Free State vs. Slave State controversy to be nonsense when it comes to the Nebraska Territory – given his conviction that its winter climate is inconsistent with operating cotton plantations.

But in political terms he understands its symbolic importance to Southerners, especially since the 36’30” precedent was ignored in declaring all of California—not just that part north of the line — to be Free.

To gain the support he needs from the South – roughly half of all Senators — Douglas now knows that the Nebraska outcome must not appear to be another California-like capitulation to those opposing slavery in the west.

1854

The Strategy Douglas Will Adopt To Secure Southern Support

To achieve his ends, Douglas continues to tout his “popsov” solution. As he says:

If there is any one principle dearer and more sacred than all others in free governments, it is that which asserts the exclusive right of a free people to form and adopt their own fundamental law, and to manage and regulate their own internal affairs and domestic institutions.

But then he extends his principle to argue that any federally imposed and arbitrary line of demarcation on slavery, like the existing 36’30” precedent, is simply inconsistent with self-government.

I never did like the system of legislation on our part to which a geographical line…should be run to establish institutions for a people…Now, a great new principle of self-government has been substituted for it, (and) I choose to cling to that principle.

Instead all issues related to slavery in the new Territories should be decided in a State Constitution, and voted on before applying for admission to the Union. Any Territories favoring a Slave State designation shall have it; and likewise for those on the Free State side.

There is, however, a fatal flaw with Douglas’ plan!

While the 1850 Compromise laws apply to the Mexican Cession Territories, they do not apply to Nebraska – a Louisiana Purchase acquisition – which is required to comply with the 36’30” line from the 1820 Missouri Compromise.

Between January 10 and March 4, 1854, the Little Giant will search for non-inflammatory ways to substitute his popular sovereignty principle for the 1820 Missouri Compromise within Nebraska.

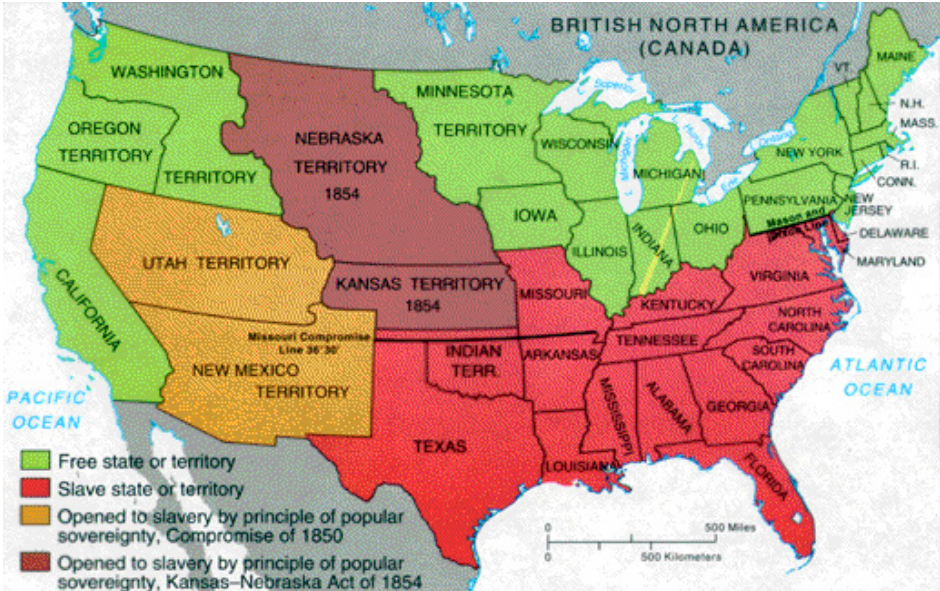

He will also hold in his pocket one more card that will add further hope for the South – the creation of a second Territory called Kansas, adjacent to the Slave State of Missouri, and perhaps prone to follow suit in a popular vote on the issue.

January 16, 1854

Questions About The 1820 Missouri Compromise Enter The Debate

Douglas’s initial Bill – calling for just the one total Nebraska Territory – is published on January 10, 1854, with an attempt (Section 21) to simply assert that the 1850 Compromise principle of popular sovereignty will be used to settle on Free vs. Slave status.

Section 21: so far as the question of slavery is concerned (the bill will) carry into practical operation…the propositions and principles established by the Compromise of 1850.

This wording draws immediate response from both sides.

The pro-slavery Kentucky Whig, Archibald Dixon, offers an Amendment on January 16, saying that the 1820 Missouri Compromise…

…shall not be construed as to apply to the Territory (in) this act, or to any other Territory of the United States; but that the citizens of the…several Territories shall be at liberty to take and hold their slaves within any of the Territories of the United States…

The Abolitionist Charles Sumner quickly counters with his own Amendment, denying Dixon’s assertion, and stating that nothing in the bill “shall be construed to abrogate or in any way contravene” the Missouri Compromise.

Taken together, these two Amendments place Douglas in the exact box he was hoping to avoid – the need to openly declare that his Bill overturns the 1820 Missouri Compromise agreement for a Territory within the Louisiana Purchase.

They are also a direct challenge to those Northern Democrats who were drawn in 1848 to the Wilmot Proviso and the Free Soil movement prohibiting slavery in the west. Whig Senator Robert Winthrop recognizes this immediately, observing that the bill will “re-inflate Free Soilism and Abolition, which have collapsed all over the country.”

Winthrop’s observation is seconded by other powerful opponents of the bill – Seward, Sumner, Wade, Chase and Giddings – all eager to sow North-South disunity among the Democrats, while finding a new political rallying cry for their floundering Whig Party.

January 21, 1854

Douglas Convinces A Shaken Pierce To Go Along With The Bill

The proposed amendments to Douglas’s original bill also cause hesitation among Pierce, his cabinet, and other Democratic Party leaders.

The President, Secretary of State Marcy and even Lewis Cass, the author of popular sovereignty, all fear the potential political backlash in the North from a repeal of the 1820 Missouri Compromise.

Douglas recognizes their resistance and appeals to Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis, to convene a meeting on January 21, 1854 at the White House to discuss the bill.

The pressure here is all on Franklin Pierce to stand by the 1850 Compromise and the principle of popular sovereignty, while holding his Southern wing in place by offering up Nebraska to an eventual vote on slavery rather than just declaring it a Free State based on the 36’30” line.

To soften concerns about “repealing” the Missouri Compromise, Douglas proposes language that says it is simply being “superseded” by the more recent legislation of 1850. To support this finesse, he also points out that Congress has already rejected extending the 36’30’ line to the west coast, thus demonstrating that it has become an outdated alternative in the west.

It remains unknown as to what extent he shares his other “sweetener” to the South – the possibly forming a Slave State in Kansas – at this critical meeting.

But after much vacillation, the January 21 session ends with Pierce now on board behind the Douglas Bill.

January 23-30, 1854

Douglas Shocks His Colleagues With A New “Kansas-Nebraska Act”

On January 23, a determined Douglas startles the Senate with a new bill he now titles The Kansas-Nebraska Act.

In it he plays his two key cards in search of Southern support:

- A definitive statement saying that the 1850 Compromise “supersedes” the 1820 Missouri Compromise, hence replacing the automatic 36’30” Free State declaration with the outcome of a popular vote; and

- The creation of a second Territory, Kansas, directly west of the Slave State of Missouri, and potentially acting as an “offset” to a Free Nebraska.

But Douglas commits a tactical error in granting a delay to open debate on the bill, and immediately lives to regret it.

It gives his opponents a chance to pounce, and they do so the following day, when several newspapers, including the abolitionist National Era, publish a counterattack, The Appeal of the Independent Democrats In Congress to the People of the United States.

Contrary to the title, the authors are not members of the Democratic Party – but rather its arch-opponents. Ohio Senator Salmon Chase takes the lead, supported by Senator Charles Sumner, Congressman Joshua Giddings and the anti-slavery philanthropist, Gerritt Smith.

The article is cast as a “duty and a public warning:”

It is our duty to warn our constituents, whenever imminent danger menaces the freedom of our institutions or the permanency of the Union.

The Bill is a “gross violation of a sacred pledge” to Freedom, defined in the Constitution and reinforced in the Missouri Compromise. It represents:

An atrocious plot…that will open up all the unorganized Territories to the ingress of slavery (and) exclude… immigrants from the old world and free laborers from our own states, and convert (them) into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves….Such a plot against humanity and democracy is monstrous and dangerous….

Chase’s Appeal is cleverly written to address all who might oppose the Douglas Bill:

- First the same odd combination he tapped into with his 1848 Free Soil Party – those hoping to abolish slavery on moral grounds and those wishing to cleanse the west of all blacks and plantation owners to keep the land to themselves.

- Second, the growing number of recent white immigrants from Europe who regard the slaves as direct competitors for the laboring jobs they need to survive.

The screed goes on to characterize Douglas as a plantation owner himself and a shill for the South, eager to please the Slave Power in exchange for its support in future presidential elections.

Needless to say, Douglas is outraged by Chase’s accusations, and he replies on January 30, in a speech laced with his usual obscenities and epithets. He denies flat out that he is the voice of the slaveholders:

I am not pro-slavery. I think it is a curse beyond computation to both white and black….(but) the integrity of this political Union is worth more to humanity than the whole black race.

And the “integrity of the Union” resides for Douglas in the simple admonishment: “let the people decide.”

He dismisses those who oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act as “abolition confederates…plotting against the cause of free government.”

May 30, 1854

The Kansas-Nebraska Act Finally Becomes Law

Douglas’s tirade on January 30 is by no means enough to silence the debate in the Senate, which continues throughout February.

Opponents hope to delay a vote, generate a public outcry against the measure and continue to vilify the Slave Power for “pulling Douglas with a string,” as the Democrat-turned-Free Soiler, Francis Preston Blair, puts it.

Secretary of State Marcy remains concerned by the political effects in New York of repealing the Missouri Compromise; John Bell and Sam Houston press on about the impact on the fate of the tribes; others begin to challenge the details and implications of popular sovereignty.

Georgia Senator Robert Toombs demands reassurance that slaves will be allowed into the new Territories during the time before a State Constitution is written and a popular vote taken – the notion being that once planted, the practice would be much harder to dislodge.

Ever the legal scholar, Chase questions whether the U.S. Constitution grants new Territories the right to decide “on their own” about slavery. After all, the original contract was the product of all the states acting together, not independently.

As times passes, the level of sectional acrimony intensifies. Along with Chase, Henry Seward becomes the target of Southern barbs, and later observes that:

It was a painful and disgraceful scene. Southern men were imperious, and Northern men abetted them. Personalities disgraced the advocates of the bill. There is no longer any dignity or honor in serving our country in the Senate of the United States.

On March 3, 1854, Douglas schedules a vote on the bill – to be preceded by one last round of debate. This begins inauspiciously around noon, when Democrat John Bell stands in opposition. Others follow, and it is not until 11:30pm that the Little Giant rises in front of a packed gallery. He speaks for three straight hours, reiterating the merits of a popular sovereignty solution, while mixing in personal invective aimed at Chase, Seward and Sumner in particular.

At 5am, after seventeen hours on the floor, the Bill passes by a margin of 37-14, with all Democrats – except Bell and Sam Houston – voting aye, while the Whigs divide along North (nay) vs. South (aye) lines. Seward recognizes the implications for his party immediately: “we no longer have any bond to Southern Whigs.”

Senate Vote On 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Bill

| Democrats | Ayes | Nays | Total |

| North | 14 | 0 | 14 |

| South | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| Total | 29 | 2 | 31 |

| Whigs | |||

| North | 0 | 12 | 12 |

| South | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Total | 8 | 12 | 20 |

| Grand Total | 37 | 14 | 51 |

Still Douglas is not yet all the way certain of victory – since the House, unlike the Senate is heavily skewed (130 to 75) toward the North.

To shepherd the measure, he again turns to his Illinois colleague, William A. Richardson, who was able to secure a 107-49 win for his earlier bill in February, 1853. With help from ex-Whig, now Unionist, Alexander Stephens, Richardson succeeds again in the House.

On May 22, 1854 the Kansas-Nebraska Act passes by a 113-93 margin.

House Vote On 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Bill

| Democrats | Ayes | Nays | Total |

| North | 44 | 42 | 86 |

| South | 57 | 2 | 59 |

| Total | 101 | 44 | 145 |

| Whigs | |||

| North | 0 | 42 | 42 |

| South | 12 | 7 | 19 |

| Total | 12 | 49 | 61 |

| Grand Total | 113 | 93 | 206 |

Pierce signs on May 30 and the bill becomes the law of the land.